By Varshini Chellapilla

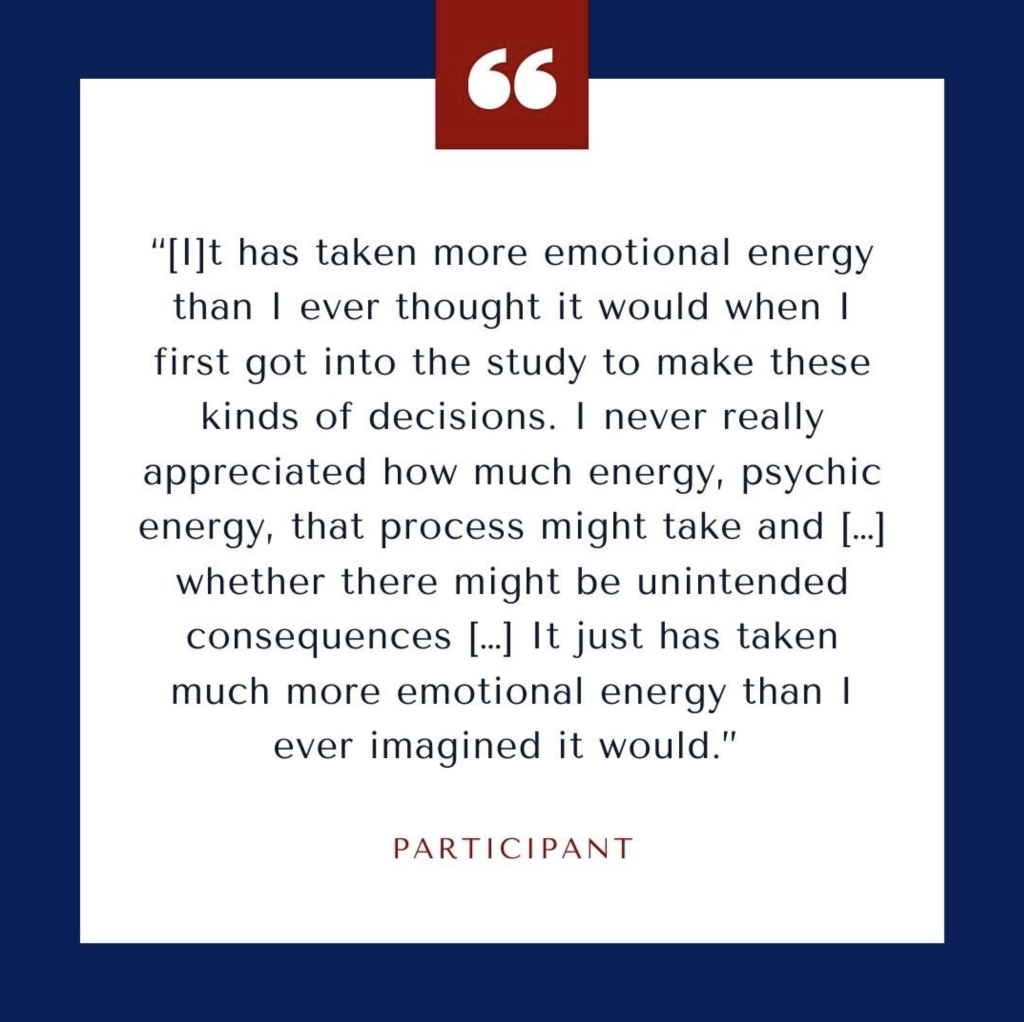

If you tested positive for a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease, whom would you tell? Why?

Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain (P3MB) researcher Emily Largent, PhD, JD, RN, conducted two qualitative studies to understand individuals’ decision-making process as they choose whom, why and how to share information regarding their Alzheimer’s disease biomarker and genetic testing results. The study, titled “‘That would be dreadful’: The ethical, legal, and social challenges of sharing your Alzheimer’s disease biomarker and genetic testing results with others,” was published in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences on May 19.

The studies were done in collaboration with three other researchers from Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain (P3MB): Shana Stites, PsyD, MS, MA; Kristin Harkins, MPH; and Jason Karlawish, MD.