If a son heard that his father had an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, based on a beta-amyloid PET scan, he would likely experience negative emotions such as sadness, worry, disappointment, and concern for his own risk of cognitive decline.

By Varshini Chellapilla and Lindsey Keener

If you were told your spouse’s risk level for developing Alzheimer’s disease, how would you react, knowing you would become their closest caregiver? If you were to be told your sibling’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, how would you react, knowing you share some genetic makeup?

Emily Largent, PhD, JD, RN, member of the Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain (P3MB), studies the implications of test results that can inform an older adult of their risk for Alzheimer’s disease later in life. But, as she explains, more people are affected by an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis than the patient alone.

And, her research showed, both older adults and their loved ones had similar responses to news of the older adult’s risk.

Emily Largent, PhD, JD, RN

In a publication on the topic, she seeks to answer how these test results impact close companions of research participants screened to determine their risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Dr. Largent interviewed the research participants’ study partners — typically spouses, adult children, siblings or friends — to qualitatively assess their reactions to learning the older adults’ risk for dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Largent’s study drew participants from Risk Evaluation and Education of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Study of Communicating Amyloid Neuroimaging (REVEAL-SCAN). This previous study enrolled cognitively unimpaired older adults (ages 65-80) with at least one close relative who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. After undergoing some tests, the participants were presented with either “elevated” or “not elevated” levels of beta-amyloid (a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease), signifying that they were at an increased risk or not at an increased risk of developing the disease, respectively.

Participants had to enroll in REVEAL-SCAN with a study partner, someone who could join the participant for a research visit and share information with the investigators about the participant’s memory and thinking. Reached by telephone, these study partners discussed topics such as their comprehension of their family member’s or friend’s beta-amyloid PET scan result, their feelings and health behaviors upon receiving the result, their future plans, and more.

“In the end, we saw that family members’ reactions were very similar to how individuals themselves react,” Dr. Largent said.

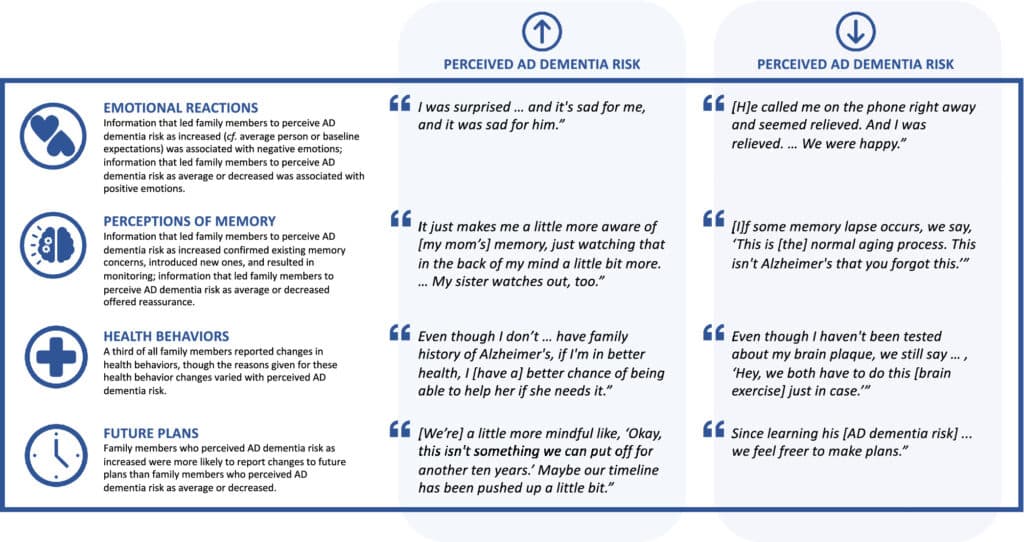

Representative quotes from family members who learned a cognitively unimpaired older adult’s beta-amyloid PET scan result and a personalized estimate of risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia by the age of 85 based on age, race, sex, and family history. (By Emily Largent)

The two most common reactions to learning a loved one’s “not elevated” beta-amyloid PET scan result were feelings of relief and happiness. If the interviewee was an immediate family member of the participant, they often reported feeling encouraged by the news, as it could indicate that their own risk might also be low.

If the interviewee received news that their friend or family member had an increased risk by virtue of an “elevated” beta-amyloid PET scan result, they experienced negative emotions such as sadness, worry, disappointment, and concern for their own risk of cognitive decline.

Dr. Largent attributed some of these negative emotions to the realization that the study partner receiving the news that they might “lose” a loved one to cognitive decline and would most likely become the primary caregiver for their partner at “elevated” risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in the near future.

This “elevated” risk news also shaped how the interviewees approached their own lives.

“Not only do [the interviewees] have similar emotional reactions to learning the dementia risk results—they engage in health behavior changes and change their own future plans in light of their sense of risk,” Dr. Largent said.

These health behavior changes may include actions like eating healthier, staying more active, and performing cognitive activities such as puzzles and memory games like Sudoku. These actions are inspired by their newfound anticipation of needing to be a cognitively capable caregiver for their loved one should they develop Alzheimer’s disease.

One piece of this research that fascinated Dr. Largent was how many interviewees favorably compared the beta-amyloid PET result to a cancer diagnosis. Though both tests can relay important medical information, the participants seemed to appreciate the delayed and uncertain nature of cognitive decline versus the immediate nature of a cancer diagnosis.

“It’s interesting to see people juxtapose cancer and Alzheimer’s disease risk. A diagnosis of cancer would be something immediate and life threatening now, whereas Alzheimer’s disease is something they’re viewing as uncertain,” said Dr. Largent.

Because the onset of Alzheimer’s disease is still years away, getting these pre-cognitive decline beta-amyloid PET scans can spark important questions about how to prepare for a shift in cognitive ability.

Where does the research go from here? Dr. Largent and her team will look at ways “to help families identify new tools and put plans into place in anticipation of the trajectory of cognitive decline,” she said.

Dr. Largent collaborated on this project with University of Pennsylvania researchers Maramawit Abera, MPH; Kristin Harkins, MPH; and Jason Karlawish, MD.