By Leah Fein and Danny Yarnall

A recent study conducted by Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain (P3MB) researcher Emily Largent, PhD, JD, RN, reveals new information on a hot-button debate in medical ethics.

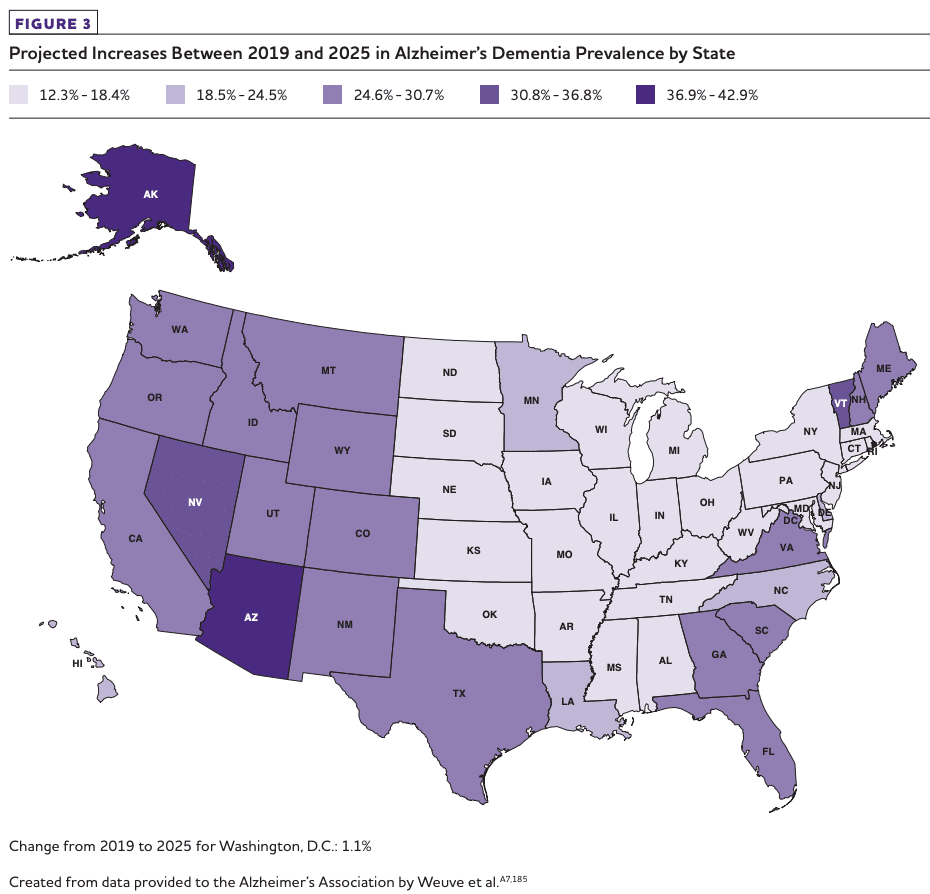

The study, published in JAMA Neurology, looked at personal perceptions of access to aid-in-dying for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia patients. With new legislation in New Jersey and Maine, by October 2019 roughly 1 in 5 Americans will live in states where doctors can prescribe lethal medication to patients with capacity who have six months or less to live.

P3MB researchers interviewed 50 older adults, most with family histories of Alzheimer’s and all with elevated levels of the Alzheimer’s disease biomarker amyloid. Amyloid confers “an increased but uncertain risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Largent told The New York Times. The P3MB researchers found that about 1 in 5 of the individuals expressed interest in aid-in-dying if they became cognitively impaired or were a burden to their families, while another 15 percent described themselves as ambivalent. Two-thirds of the group would not choose aid-in-dying for themselves.