By Danny Yarnall

Medicare’s open-enrollment period for 2020 is already a month underway and many older Americans are weighing plans ahead of the December 7 deadline. But outside of normal year-to-year increases in out-of-pocket costs and premiums is a staggering difference for Medicare beneficiaries with dementia.

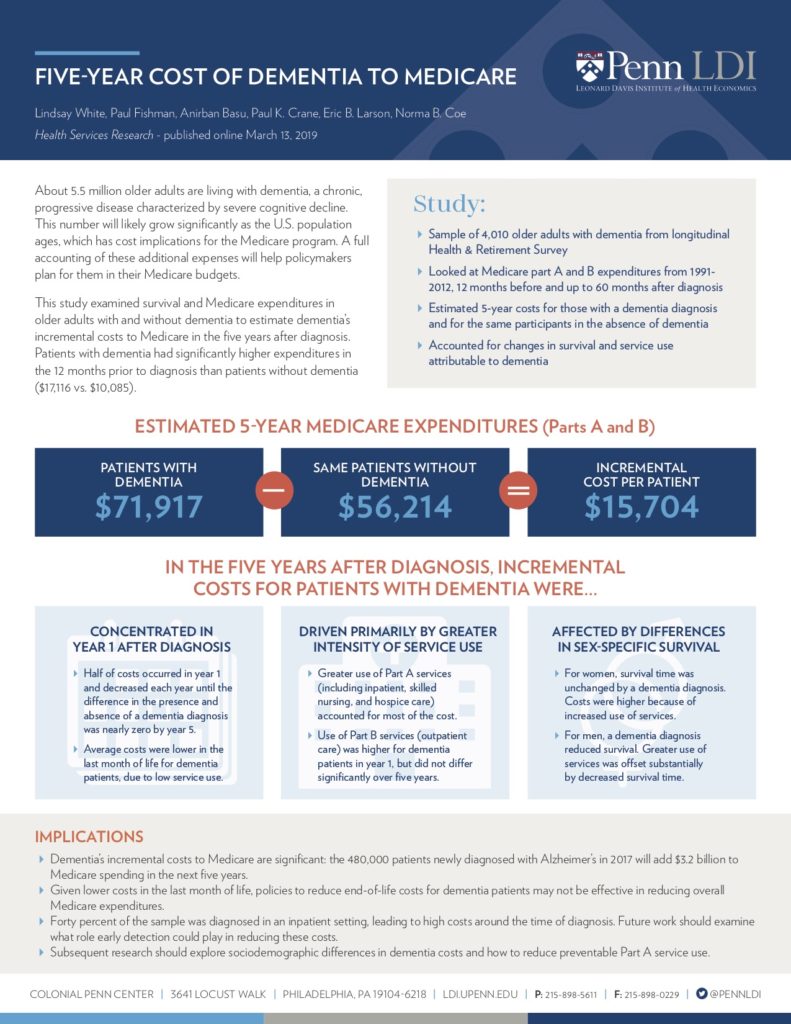

Last April, Health Services Research published a study that used 20 years of Medicare expenditures to estimate that Medicare spends nearly $16,000 more on patients with dementia than other Medicare beneficiaries.

This is an “incremental cost” or the extra cost per person specifically due to their dementia. Small, in terms of gross Medicare spending, but an amount that still matters in the long run. The incremental cost accounts for over one-fifth of all Medicare spending per patient with dementia, a disease that affects 5.8 million Americans.

“We need to know how much this costs so we can be prepared,” said Norma B. Coe, PhD, lead author of the study and an associate professor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Norma Coe speaks at the 7th Annual Penn Health Policy Retreat, co-sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy (MEHP), and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. (Photo by Hoag Levins)

The study looked at the spending among 4,000 beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part A and B, what is known as traditional Medicare, diagnosed with dementia between 1991-2012 from 12 months before through five years after their initial dementia diagnosis.

Dr. Coe and her colleagues found the majority of costs come within the first two years of diagnosis, and the bulk of the spending was for services such as inpatient, skilled nursing, and hospice care that fall under Medicare Part A. Medicare Part B, which includes doctor’s visits, did not feature as prominently as additional costs on Medicare’s ledger for patients with dementia.

A notable fact is that a large portion of patients were diagnosed in an inpatient setting, a hospital stay.

“This is probably not how the disease is occurring,” Dr. Coe said. This is likely after cognitive decline started, relying on a serious event to diagnose dementia.

Dr. Coe and her colleagues estimated the 480,000 people who received an Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 2017 alone will add $3.2 billion in Medicare spending by 2022 and that number is only growing.

The rising cost of dementia care will continue to add strain to Medicare as a hundreds of thousands of Americans are diagnosed every year. But this isn’t an issue for just Medicare.

In ongoing work, Dr. Coe and her colleagues are looking at the wider financial impact of dementia. The disease is costing another $16,000 in Medicaid expenditures, plus $7,000-8,000 in out of pocket costs, on average, over the same five-year projection.

Beyond the cost of hospitalization and medical care are the direct and indirect costs of family caregiving.

For the median daughter caring for her mother — you would have to give her $180,000 over two years to make her just as well-off as if she didn’t provide care according to another study published by Dr. Coe. This, she believes, is where the true cost dementia care lies.

“There’s so many holes in the system…the fact that family caregiving costs [180,000] completely trumps anything we’re talking about with Medicare expenditures,” said Dr. Coe.

This all seems daunting for a disease that has no cure or effective treatment as of yet, but it is far from a lost cause. Coe hopes this study and the larger body of work put a focus on patching those holes that put the cost on families.

Efforts that focus on early diagnosis and breaking the stigma around the disease can keep older Americans out of the hospital — and reduce the need for many of the Medicare Part A services, where the brunt of the spending occurs — and provide them with the care they need sooner. This can cut back on Medicare costs and help families manage the disease more effectively, Dr. Coe explains.

“If you can avoid that ‘crisis situation’ at the time of diagnosis you can both save money and likely improve patients’ well-being. It’s a start,” said Dr. Coe.