By Victor Ekuta, MD

Penn Memory Center Clark Scholar

I was in my 3rd year of medical school when I first heard the phrase that “time is brain.” Coined in a 1993 editorial by Dr. Camilo Gomez, this pivotal concept emphasizes the critical importance of early intervention in preserving brain health after a stroke. “Unquestionably,” Dr. Gomez wrote, “the longer therapy is delayed, the lesser the chance that it will be successful, and early intervention will probably be a major determining factor in the limitation of the damage of neurons.”

Recent advancements in stroke neuroimaging have not only affirmed but quantified this urgency. For every untreated minute in an ischemic stroke, the average patient sheds a staggering 1.9 million neurons. For every hour, the loss of neurons is equivalent to almost 3.6 years of normal aging. In essence, this reaffirms the fundamental truth: time is, undeniably, brain!

Victor Ekuta, MD

The adage “time is brain” takes on profound meaning in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. The development of Alzheimer’s disease spans years, beginning with the insidious accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles in neurons. These disruptive deposits wreak havoc on synapses, the communication bridges between brain cells, leading to dysfunction and cognitive decline. Therefore, timely intervention emerges as an essential linchpin for mitigating brain damage and preserving overall brain health in Alzheimer’s disease.

Today, the field of Alzheimer’s disease is perched on the edge of transformative interventions, marking a crucial turning point. Aducanumab, developed by Biogen, achieved FDA approval in June 2021—a groundbreaking but controversial moment in Alzheimer’s therapeutics. More recently, lecanemab, born from the collaboration between Eisai and Biogen, gained full FDA approval in July 2023 —a beacon of promise in slowing Alzheimer’s progression.

Lecanemab, a groundbreaking monoclonal antibody, holds the promise to intercept the silent disruption caused by beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease by slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. In a clinical trial involving nearly 1,800 early-stage Alzheimer’s patients, the drug slowed the progression of the disease in those who received biweekly infusions, compared with those given a placebo.

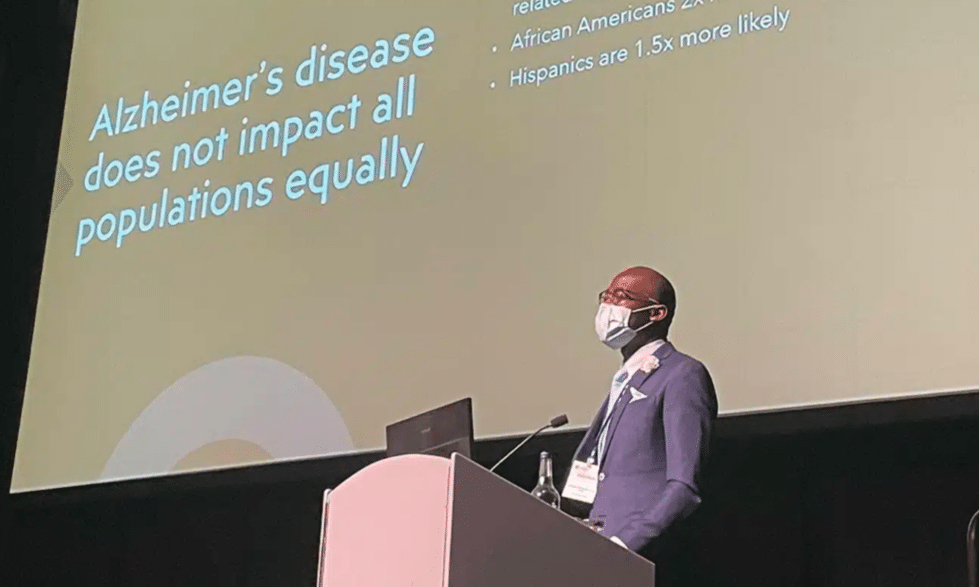

Yet, within this narrative of hope, a disconcerting truth surfaces: the axiom “time is brain” may not wield equal weight for Black patients. A staggering 6.7 million Americans, aged 65 and older, grapple with Alzheimer’s today. By 2060, this number is set to double, disproportionately affecting Black Americans. A disconcerting trend reveals that older African Americans bear a heavier burden of cognitive impairment, a stark injustice demanding our attention.

Despite this awareness, recent research unfurls a disheartening tapestry of challenges impeding timely intervention for racial and ethnic minorities. These challenges extend beyond statistical disparities and include underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, treatment disparities, and significant underrepresentation in clinical trials.

Victor Ekuta, MD

So how exactly does lecanemab measure up? The trial’s limited representation of Black participants—only 20 out of 859—and the exclusion of some due to low amyloid levels in PET scans raise concerns. The study’s design, which screened out participants based on amyloid levels, may unintentionally exacerbate disparities, especially considering that Black patients often receive late-stage diagnoses that may hinder their eligibility for early-stage treatments like lecanemab.

The importance of diversifying clinical trials is not a distant concept for me. In the spring of 2021, I took part in the MIT linQ Catalyst Healthcare Innovation Fellowship—a unique program that brings together experts from various fields to collaboratively identify and validate unmet medical and health-related needs, explore new project opportunities, and develop action plans. Tasked with identifying an unmet need, I embarked on a search for a project and eventually stumbled upon a striking case study of “systemic racism in miniature”—pulse oximeters.

A pulse oximeter measures oxygen in blood.

Pulse oximeters are ubiquitous in medicine. Thousands of times a day, healthcare workers use them to measure the percentage of oxygen in blood and make vital treatment decisions for conditions such as asthma, COPD, and now COVID-19. These devices were presumed to be unbiased tools, functioning uniformly across different racial and ethnic groups. Yet, both my own research and that of others revealed a disturbing reality: pulse oximeters were less accurate in patients with darker skin tones, a deficiency that not only can but already has led to potential misdiagnoses, delayed treatments, and compromised patient care.

As a Black physician and neuroscientist, that pivotal moment stands out because of the crucial role of oxygen in brain health. The presence of racial bias in a tool meant to measure such a vital substance for the brain’s well-being underscores just how easily a lack of diversity in testing novel innovations can go on to compromise the brain health of an entire community.

The story of the pulse oximeter serves as a cautionary reminder that the innovations we develop today will invariably shape the brain health of tomorrow. It is imperative we remain vigilant in addressing and rectifying the barriers present in our field to ensure that the future of tomorrow will be one of equity and inclusion in brain health. Only then can we ensure that everyone reaps the benefits of new therapies.

In the tapestry of healthcare, every strand, every intervention, must be woven with a commitment to equity. The clock is ticking, not just for individuals but for our collective conscience. The transformative potential of medical breakthroughs should uplift all, erasing the shadows of disparity and ensuring that, for every individual, “time is brain” is not just a phrase but an unequivocal reality.

References:

- Gomez CR. Editorial: Time is brain! J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1993;3(1):1-2. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80125-9. Epub 2010 Jun 10. PMID: 26487071.

- Saver JL. Time is brain–quantified. Stroke. 2006 Jan;37(1):263-6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000196957.55928.ab. Epub 2005 Dec 8. PMID: 16339467.

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2212948#article_citing_articles