By Meghan McCarthy

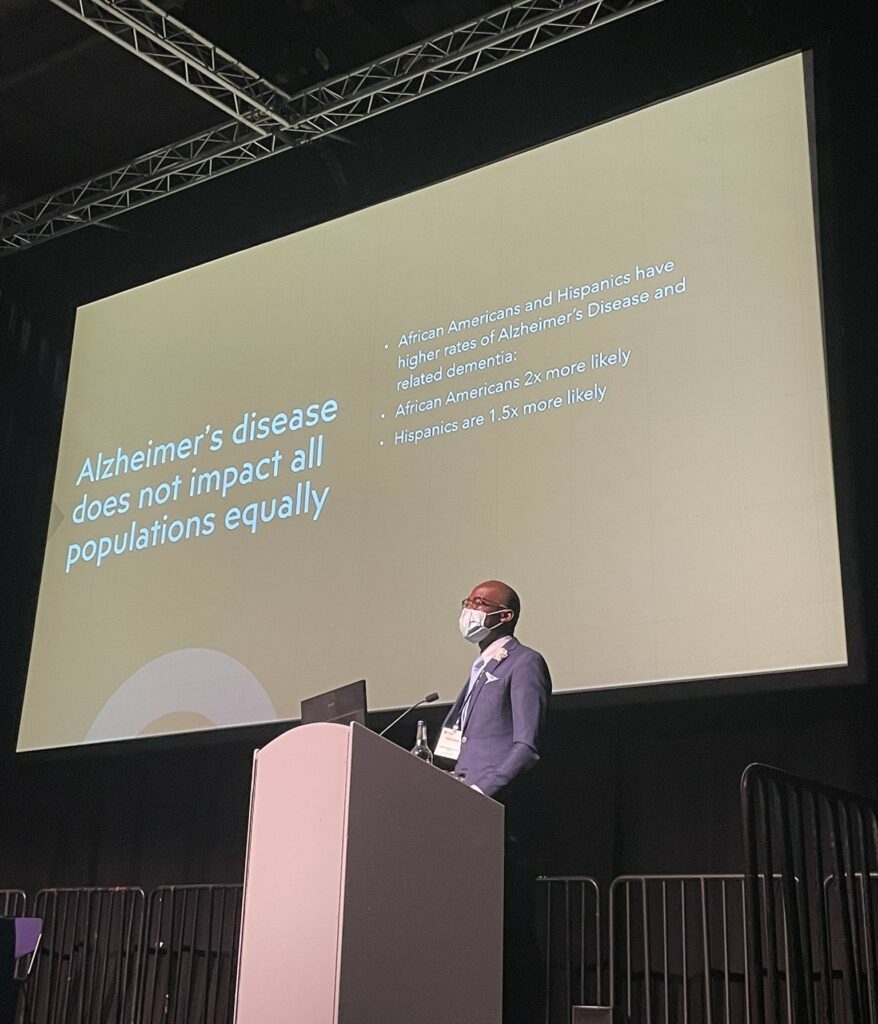

The average African American is twice as likely as a white adult to develop dementia, yet is 35% less likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).

This disparity is a result of generations of mistreatment, mistrust, and discrimination. It serves as one of many examples which illustrate the need for change within the ADRD space.

For Victor Ekuta, a 2022 Penn Memory Center (PMC) Clark Scholar, personal experience with such discrimination launched a professional passion for health equity.

Ekuta was born in Nigeria but moved with his family to the U.S. when he was a toddler. Throughout his childhood, the family relocated numerous times. With each introduction as “the new kid,” Ekuta honed in on his own identity as a Nigerian-American.

“Growing up with a multicultural background allowed me to understand the value of your own identity and sharing that with others,” said Ekuta. “We all have things we can contribute to other people’s learning.”

Yet, despite being a good student, Ekuta often heard teachers remark he was less capable than classmates.

“I always felt the need to prove myself, and because of my experiences, want to create opportunities for people who look like me,” said Ekuta.

Ekuta is part of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Office of Engineering Outreach program, which offers free science enrichment programs for high school students.

Ekuta is also a Black Men’s Brain Health Scholar, a collaboration between the Alzheimer’s Association and NFL Alumni Association that works to increase the number of Black males involved in brain research and improve the skills of researchers working with this population.

As a third year-medical student at UC San Diego, Ekuta has applied his value of health equity into his medical research involvements.

“When I think of health equity, I think of equal access to health opportunities from people of all different backgrounds,” said Ekuta.

The uneven diagnosis rates between racial groups are often due to differences in lifestyle and accessible healthcare.

Victor Ekuta

“It comes down to social determinants of health: where do our patients live, work, eat,” said Ekuta. “We need to address these factors that contribute to disparities in order to create a more equitable healthcare environment.”

A major barrier to equitable clinical care is a lack of inclusion in research.

“Research suggests that biomarkers for disease may be different between African Americans and Whites,” said Ekuta. “Research I’m involved with is aimed at finding those differences, and using them to improve diagnostics for underrepresented populations.”

Often, underrepresented groups are hesitant to join research studies. This can be as a result of distrust due to previous experiences of racism or lack of cultural awareness by researchers when recruiting, amongst many factors.

“We need to change communication in how we recruit people for research studies in order to reflect diverse populations,” said Ekuta. “We also need to work towards educating people about the disparities that exist.”

One way to do this is through educating minorities on lifestyle changes that promote healthy brain aging.

Ultimately, Ekuta is optimistic about the momentum behind current and future initiatives.

“I believe organizations are trying to make more of an effort to at least discuss equity and social just issues, and develop new strategies for inclusion of underrepresented populations,” said Ekuta. “I’m hoping that this change is sustained, and that people will continue wanting to talk about these issues.

Victor Ekuta is a third-year medical student at UC San Diego and a Clark Scholar at the Penn Memory Center. While working with Roy Hamilton, MD, MS, Victor was a minority scholar in aging research. He is a current instructor for the MIT Office of Engineering Outreach Program, and a Black Men’s Brain Health Scholar.