By Erin Alessandroni

The stigma associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) often presents patients and their families with psychological and social challenges. Penn Memory Center provides steps clinicians can take to minimize this stigma in a paper published to Practical Neurology.

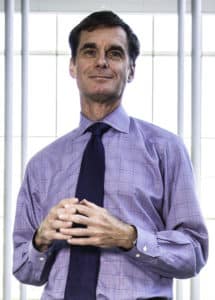

PMC Scholar Shana D. Stites, PsyD, MS, MA and PMC Co-Director Jason Karlawish, MD describe stigma’s consequences on both how a patient and caregiver react to a diagnosis (“internalized stigma”) and how the community treats the diagnosed in discriminatory or patronizing ways (“public stigma”). Additionally, a third type of stigma called “spillover stigma” can affect caregivers and family members who become associated with presumed negative societal traits.

Stereotypes such as these impede progress in research by discouraging participation. This is why neurologists and other clinicians should take the steps discussed by Drs. Stites and Karlawish to minimize this stigma.

The first is to personalize the experience of each patient, avoiding stereotypes about those affected. This approach saves patients from stereotype threat, through which patients can conform to the stereotypes associated with their disease, hindering their ability to function and quality of life.

Next, the authors suggest asking patients specific questions, correcting misinformation, and adjusting expectations to be more accurate so that patients and family members avoid unsubstantiated concerns.

A 2015 national survey led by Penn Memory Center researchers, including Dr. Karlawish, found that it is the expected deterioration of a person’s mind that contributes to negative feelings and stigma, not necessarily the disease itself. This highlights the importance of correcting misconceptions about the disease.

In addition, a recent research study led by Dr. Stites concluded that people expect a person with AD to be discriminated against by employers, excluded from medical decision-making, and have their health insurance limited due to documentation of their diagnosis.

Clinicians should support dignity by using person-centered terms and avoiding “absolutes,” leaving room for individualized experiences. They should also help individuals access self-care strategies such as a healthy lifestyle, medication adherence, and proper hygiene practices.

Drs. Stites and Karlawish suggest encouraging the patient and caregiver to become engaged and involved through activities, studies, and programs in order to minimize the effects of stigma.

“This is an exciting time in Alzheimer’s research,” Dr. Stites told the Alzheimer’s Prevention Bulletin. “We have opportunities to break down the stereotypes, put a face to this disease, and show the world how you can live better, even with this diagnosis.”

For the full article published to Practical Neurology, click here.