Biomarkers and new therapies have revolutionized Alzheimer’s care. In the United States, doctors can now prescribe two new anti-amyloid treatments that slow cognitive decline. However, in a recent essay Jason Karlawish, MD, and Joshua Grill, PhD, warn that treatment is overshadowing the value of delivering a comprehensive diagnosis and prognosis to patients and their families.

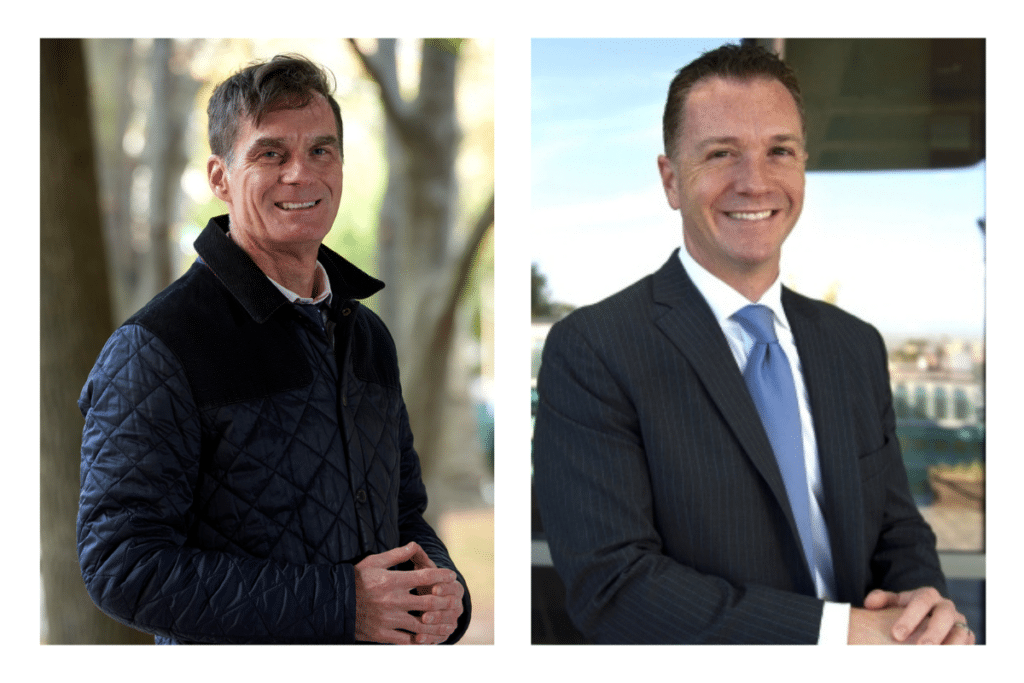

“Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers and The Tyranny of Treatment,” published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity and eBioMedicine, highlights a critical issue. Diagnostic tests are increasingly tailored to meet the needs of therapies, particularly new anti-amyloid treatments, rather than being used to support the patient. These treatments – lecanemab and donanemab – are encouraging, but Drs. Karlawish and Grill emphasize access to these treatments shouldn’t dictate the availability and use of diagnostic tools.

The role of biomarkers in Alzheimer’s diagnosis and prognosis

Historically, a definitive Alzheimer’s diagnosis was possible only after death, using a brain autopsy. Biomarker tests that measure beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles have changed this. Today, using PET scans and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests clinicians can make a precise diagnosis during a patient’s life. The results can also help inform prognosis. A positive amyloid PET scan in a patient with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), for example, strongly predicts progression to dementia.

And yet, for all their potential, biomarkers are not widely used in clinical practice. In the United States, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services which administers the Medicare benefit only recently approved coverage for an amyloid PET scan, a decision driven largely by the FDA’s approval of new anti-amyloid therapies (the scan is needed to determine whether a patient is appropriate for treatment). This decision highlights the tyranny of treatment: care is treatment-driven, with diagnostic tests valued primarily to identify candidates for these therapies, in particular persons who fit within the range of the MCI and mild stage of dementia stages. Moreover, tau imaging – though FDA approved and a valuable tool to stage the spread of Alzheimer’s disease – is not needed to prescribe the new therapies, inform prognosis or stage. It is essentially relegated to research contexts.

The missing element: Comprehensive patient care

Drs. Karlawish and Grill emphasize precision medicine that targets treatments are valuable, but diagnosis and prognosis should be central to patient care. Patients and their families deserve to understand the causes of their cognitive impairments and what to expect in the future. This information is vital for informed decisions about care, planning, and quality of life.

The authors also point out that current biomarker testing often simplifies important information into simple summaries of “positive” or “negative” categories. This misses the detailed information these tests can provide, which can guide patient care even without treatment.

The path forward: A call for a republic of care

The essay underscores the need to break the “tyranny of treatment” and establish a “republic of care,” where the full spectrum of patient needs—diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic—is valued and addressed. This shift, Drs. Karlawish and Grill suggest, is essential to optimize outcomes for all patients and their families.