By Meghan McCarthy

In a recently published manuscript, researchers at the Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration (FTD) Center found that African American patients and those of low socioeconomic status are significantly less likely to access neurogenetic evaluation compared to White patients.

These findings exemplify systemic barriers and health inequities and have a direct impact on the equitable inclusion of marginalized groups in clinical trials related to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs).

Neurogenetic evaluation, which includes genetic counseling and testing, is used for diagnostics and disease risk predictions.

In the world of ADRDs, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is one example that has hereditary causes. Thus, neurogenetic evaluation can be very helpful for patients, their families, and clinicians.

Aaron Baldwin, MS, LCGC, a genetic counselor in the Department of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, noted a lack of diversity in their clinic. This observation led Baldwin and his team to explore whether demographic differences affect patient access to neurogenetic evaluation.

“We realized there is not any data about genetic disparities in the neurology subspeciality,” Baldwin said. “That led us to moving forward with trying to understand the issues at play within our own patient population.”

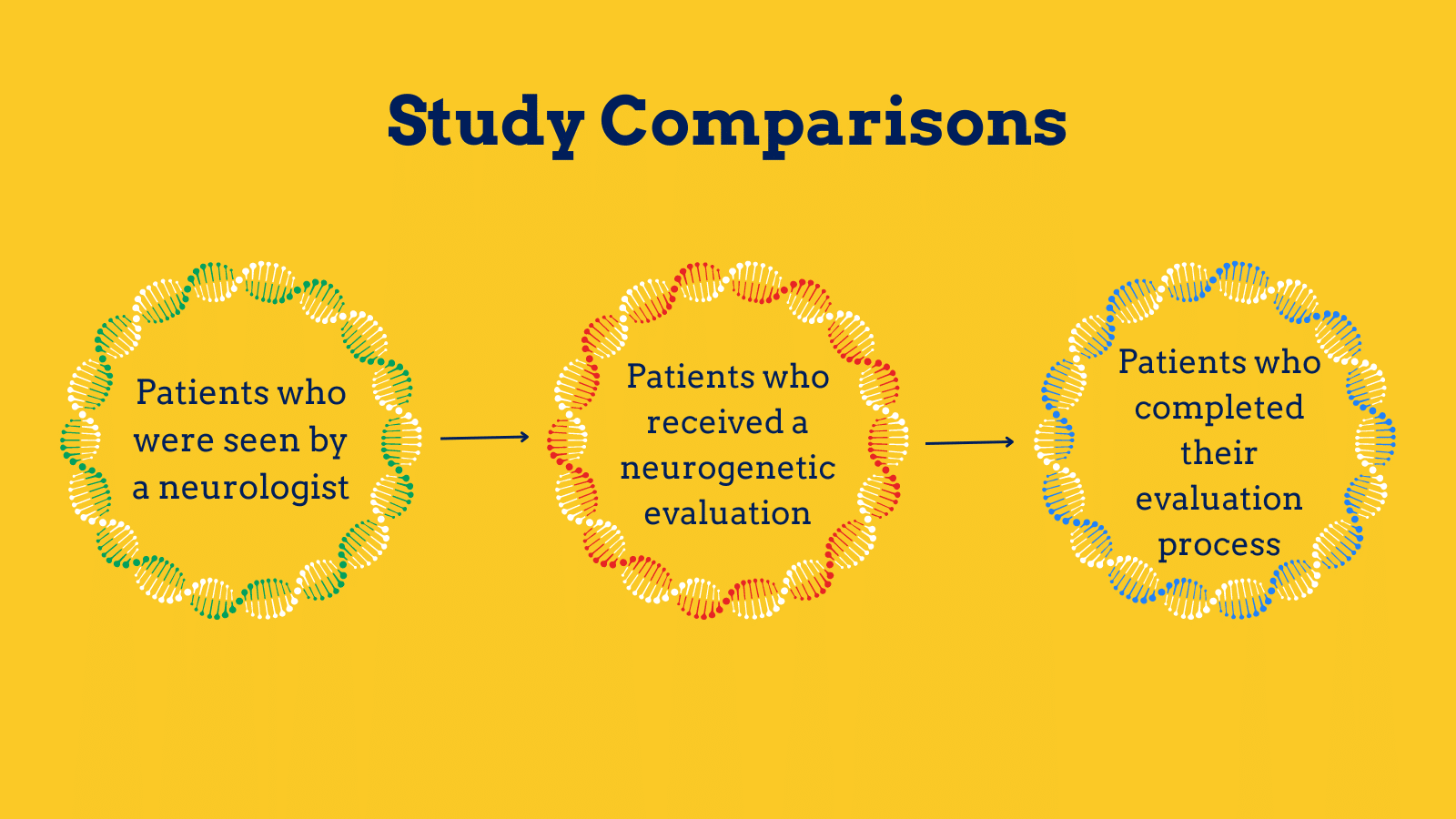

To begin, the team assessed almost 130,000 patients seen between 2015 and 2022. They found that approximately two percent of patients seen by a neurologist were then seen for genetic counseling.

Several structural and social determinants of health (SSDoH) impact one another. For example, patients of low-income status are also less likely to have health insurance and may live farther from medical care.

“There is a synergistic impact on a patient, especially one from a demographic group that is associated with lower socioeconomic status,” Baldwin said.

To address this, Baldwin and his team compared differences based on race and ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status to see if any affected the likelihood of patients undergoing neurogenetic evaluation.

Ultimately, the team found that based on ethnicity alone, African American patients were around 50 percent less likely to move forward with a neurogenetic evaluation after seeing a neurologist compared to White patients.

The team did not find a significant differences in evaluations between Latino and White individuals or between genders. They also did not find significant differences in the outcome of diagnostic results between groups.

“We thought that was important,” Baldwin said. “There’s so much research pointing to the need for diverse groups to be included in clinical trials. Our studies show that at least in neurology, there was no difference regardless of background, which just points to the fact that everyone should be offered and have access to these kinds of services.”

Beyond race, patients of low socioeconomic status and those with Medicaid or Medicare were also less likely to be seen compared to individuals of higher socioeconomic status and those with private insurance.

In the patients who are seen for an evaluation, all groups had a similar likelihood of completing the process.

“For a patient to ‘complete’ the process, patients see a genetic counselor, send off a sample for testing, have that sample tested, and then have another clinic visit to review results and any family member implications,” Baldwin said.

Such findings have important implications. For example, having a diagnosis confirmed through genetic testing is often a requirement for inclusion in clinical trials.

In an era of fast-paced drug and gene therapy development, recognizing factors that impact access to neurogenetic evaluation is the first step towards understanding how to equalize research inclusion.

“We felt like it was really important to call this out and understand it in order to reduce downstream impact on these groups, which have already been marginalized and minoritized over time,” Baldwin said.

While the team was able to compare demographics between patients, they also recognize several factors may influence patient access to neurogenetic evaluation outside what was studied.

Unreliable referral processes, mistrust between patients and providers, and implicit biases amongst providers may also play a role in the found disparities.

“These marginalized and minoritized groups might just be less likely to trust moving forward with a genetic counselor or genetic evaluation.” Baldwin said. “There is historical mistrust so our goal is to come out and say: this testing is still valuable.”

Ultimately, Baldwin believes this study lays an important foundation for informing clinicians and future research on such disparities.

“We’re hoping that the general neurology community is more aware of this difference,” Baldwin said. “It can have downstream impacts, not just for a patient, but also for their family, brothers, sisters, and future children.”

To read the full article, please click here.

Aaron Baldwin MS, LCGC is a staff genetic counselor in the Department of Neurology at The University of Pennsylvania, providing patient services in both the epilepsy and leukodystrophy clinics. Additionally, his role includes working towards research-based opportunities and studies with a focus on reducing healthcare disparities. Before starting this role, Aaron worked at GeneDx, a genetic diagnostic laboratory, as both a lab lead and later a genetic counseling assistant with the neurology team. He completed his genetic counseling training at both Augustana University in Sioux Falls, South Dakota and The University of California – San Diego in San Diego, California. His focus points include identification of genetic causes of different neurological disorders along as well as careful examination of the impact that racial and ethnic background can have on medical outcomes for underrepresented minority populations in the United States.