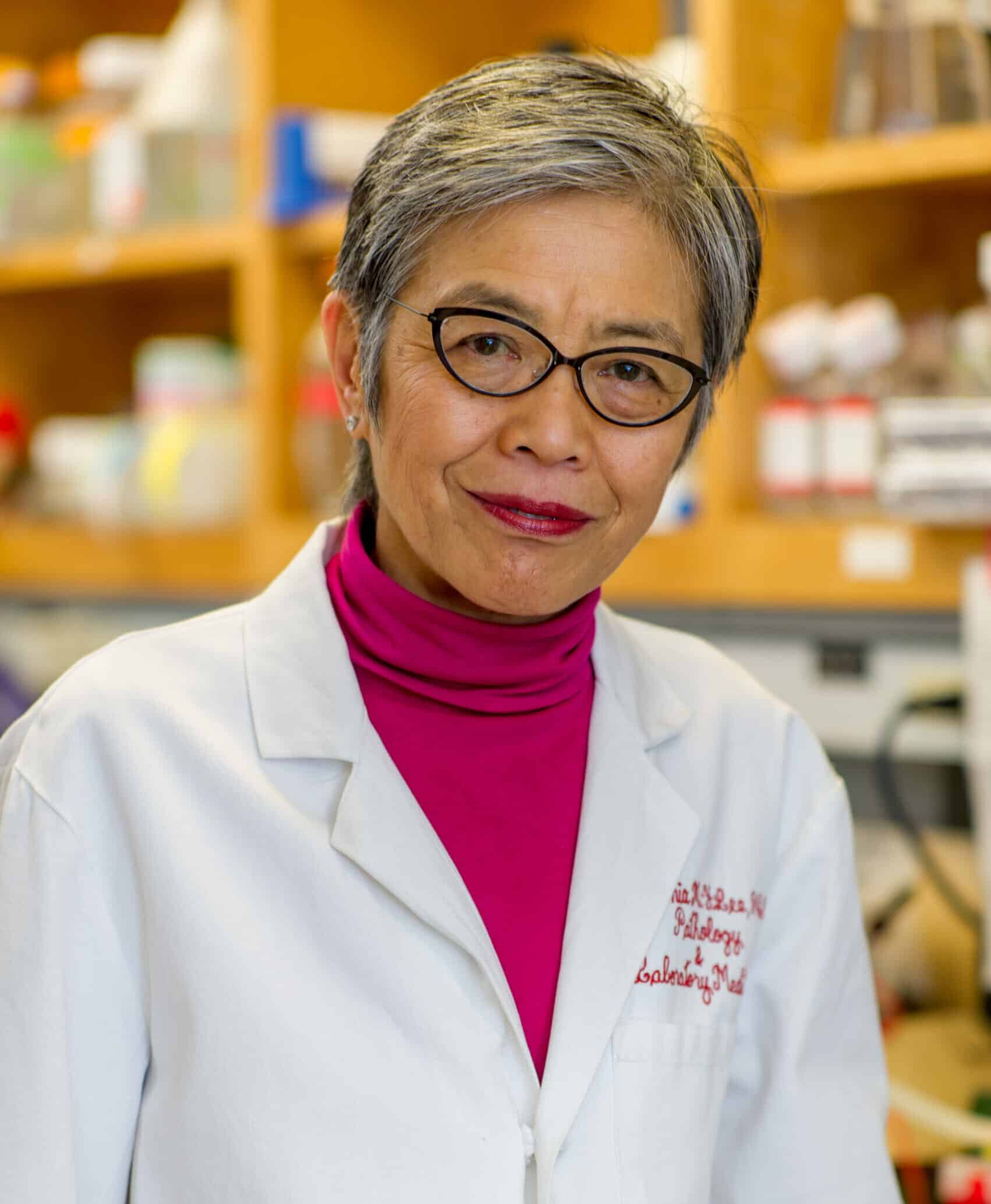

Viginia Man-Yee Lee

By Meghan McCarthy

Virginia Man-Yee Lee, PhD, MSc, MBA, is one of the world’s most recognized and decorated researchers.

As director of the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR) at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Lee studies the role of different proteins in various neurodegenerative disorders of aging, including Alzheimer’s disease. And for each of the more than 1,000 research publications which she has authored, she has also been cited in nearly 200,000 articles by others.

In recognition of that work, Research.com ranked her among the world’s top 100 scientists and the No. 2 female scientist. She has been awarded dozens of academic honors, notably the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences and its associated $3 million grant from a selection committee including Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Sergey Brin.

Yet, throughout her life, Dr. Lee has had to prove her value.

To her mother.

To her employers.

To the entire scientific community.

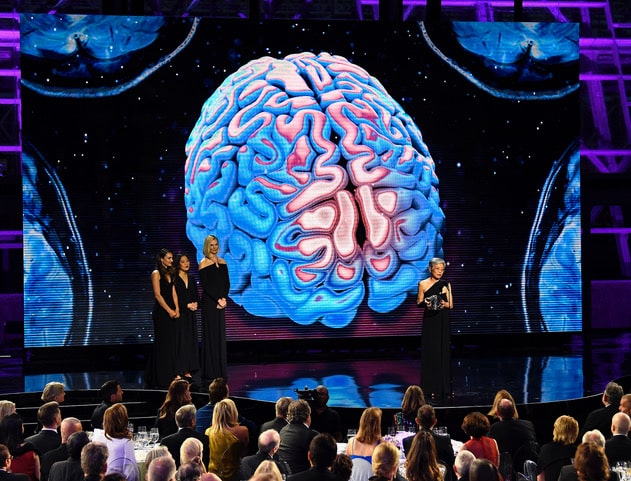

She earned the Breakthrough Prize in 2020, but she says her true breakthrough came when she began believing in herself.

Dr. Lee receiving Breakthrough Prize (Photo by Breakthrough Prize Foundation)

A Predetermined Future

Lee’s mother became pregnant with her shortly after the second World War. Originally from mainland China, her family was on the run from Japanese communists at the time.

Having two sons already, her mother didn’t want to have another child.

Sons merited value. A value so high that her mother had already fulfilled her duty, or obligation, to have two. Without the use of ultrasounds, she had no way of knowing what gender the third child was.

On the chance that she was pregnant with a daughter, which gave no value, having the child wasn’t worth the risk.

“But my father wouldn’t hear of it. So, I was born at the roadside as they traveled to Chongqing.”

As she grew, Lee aimed to prove her value. When her mother encouraged musical studies, she obliged and moved to London to begin piano training at the Royal Academy of Music.

“At the time in Chinese culture, the general idea would be for women to have some sort of education. But if you’re from a good family, you get married, have children, and live happily ever after,” said Lee. “I had no pressure to have a career.”

Dr. Lee in high school with her teachers and classmates

Lee’s future appeared predetermined. She had the pedigree and education; all that was left was marriage.

In a time where cultural norms pressured many women to say yes, Lee had to find the bravery to say no.

So, she dropped out of the Royal Academy of Music. Supported by her father, she pursued her bachelor’s degree and master’s degree at the University of London. She then received her PhD in biochemistry from the University of California at San Francisco.

Ultimately, Lee moved to the U.S. for her post-doc training at Boston Children’s Hospital, where she met the man who would become her husband, John Trojanowski, MD, PhD, a renowned scientist in his own right. Nearly three years later, the couple married and moved to Philadelphia.

While he completed his residency, Lee struggled to break into the scientific community.

“John’s boss told me that if I got a grant, I had a job,” said Lee. “But as a woman, I didn’t have mentorship. More importantly, I didn’t know how good I was.”

As a woman in science, Lee had to prove her value. Again.

Discouraged, Lee pursued an executive MBA at Wharton as a fallback plan. During her first year, she received two prestigious grants.

“I said to myself, I can,” said Lee. “I can go to school full time. I can run my grants. Clearly, I can sustain myself as a scientist.”

A breakthrough.

Dr. Lee and her late husband, John Trojanowski, MD, PhD.

‘I can’

With I can as her mantra, Dr. Lee slowly gained momentum in grants and awards and earned respect from her colleagues.

“A large part of where I am today is that I’ve had a very long career,” said Lee. “In two months, I’ll be 77, and I’m still working.”

Lee believes her greatest accomplishment is the discovery of TDP-43, a protein that binds to DNA and can be harmful when built up in the brain.

“What was so fantastic is that people were able to repeat our research, and now are coming up with new applications and ways to use it,” said Lee.

Beyond TDP-43, Lee values mentorship, something she and most female scientists weren’t offered at the start of her career.

Now, her goal is to gather and train the next generation of disease scientists at Penn.

As a mentor and inspiration to rising female scientists, Lee’s advice is simple:

“Your life is going to be very busy, but it’s all doable,” said Lee. “Even if you take time off for family life, remember that careers are very long. Take the time you need, and know that you can work for a long time.”

From the roadside of Chongqing to being recognized as one of the most esteemed scientists in the world, she believed she could, so she did.