By Meghan McCarthy

Editor’s Note: In light of the 2024 PennAITech Symposium, this article is a part of ongoing coverage on the intersection of technology and dementia. Names have been changed to protect PMC patient privacy. We sincerely thank the family involved in sharing their story with our community.

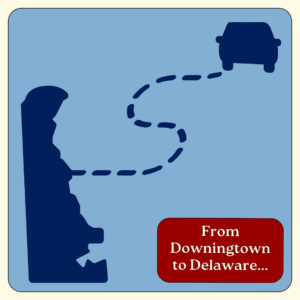

When Zachary Collins set out for a drive to Downingtown, the route was seemingly simple. Twenty miles west of his home, neither he nor his wife, Mary, thought much of the outing.

Until Zachary found himself in Delaware.

It was then that the pair fully appreciated the Waze app.

Two years ago, Zachary was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by Penn Memory Center (PMC) co-director Jason Karlawish, MD. He is still in the early stages of the disease.

The diagnosis prompted a series of questions for the couple. At the forefront, Mary wrestled with a question many caregivers struggle to answer: How can she support her husband’s independence while keeping him safe?

Often, progression of AD involves a declined ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). Common ADL examples include managing finances, cooking and eating regularly, and driving.

The timeline of ADL decline is extremely individualized. For caregivers, this requires fluidity in assessing when loved ones may need more assistance in their care.

In Zachary’s case, where disease progression has been slow, his ADLs are mostly unchanged. Since his diagnosis, for example, he has continued to drive independently.

“My husband has always been a car guy,” said Mary. “It’s going to be hard for him to give up driving. We know that’s in the future. Right now, with the help of technology, we’re pleased that we can make this work for as long as we have.”

On most days, Zachary can drive to familiar locations with ease. However, he does have occasional moments of confusion.

With his diagnosis, Mary and Zachary considered tools that could enhance Zachary’s safety when driving independently. Ultimately, Mary decided to integrate technology into his care plan.

While finding a right and preferred app took time, the couple was committed to testing out different options.

Zachary started with Google Maps for directions but didn’t like the format. He then moved to asking Siri questions about his route. After getting a new car equipped with an integrated Waze navigation system in the center console, Waze has become his favorite.

Waze is a navigation app that integrates real-time data from users to offer routes with real-time traffic updates, turn-by-turn voice guidance, and customizable alert systems. Users that opt-in are also able to track friends and family, and route specification like ‘highway backroad only’ are also possible.

While Zachary is behind the wheel, Waze has given Mary immense peace of mind.

“Recently I looked at the map and it was extremely complicated,” said Mary. “There were a number of turns, multiple intersections, and I was convinced I’d have to go with him. Sure enough, he went and got back all by himself.”

Zachary and Mary also use Life360, which is a GPS sharing service that allows loved ones to track one another.

When Zachary accidentally drove to Delaware, he called Mary disoriented. Instantly, Mary tracked his location through Life360 and redirected him home using Waze.

“These apps aren’t just convenient,” said Mary. “They can be a real lifesaver, especially in helping keep an individual’s independence and ability to function.”

For caregivers, this scenario is either familiar or unsurprising.

While not calculated in recent years, it’s estimated that 20 to 30 percent of AD patients experience becoming lost while driving.

Perhaps your loved one’s meticulous financial management has shifted into forgotten bills. Or, while usually organized, they now often lose track of which medications they have taken. In these situations, caregiver support groups, or devices and applications, serve as a crucial support tool for families like the Collins though the decision-making process surrounding patient safety demands ongoing deliberation and professional consultation. For instance, as Zachary’s symptoms progress, driving independently may no longer be safe.

Before integrating apps, it is important to discuss driving with your care team early and often. Beyond symptoms of cognitive decline, some diseases that cause dementia can alter visual perception and impact necessary driving skills like depth perception and peripheral vision.

At PMC, driving appropriateness is assessed on a case-by-case basis.

“It’s great that some folks in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease are able to use apps like Waze to stay independent,” said Alison Lynn, MSW, LCSW, PMC director of social work. “However, this won’t apply to everyone. Issues with way-finding/getting lost are only one reason why someone with AD may need to stop driving. Many of our most complex cognitive processes, such as planning, multitasking, and judgment, are also involved in driving, and cannot be replaced by an app.”

Determining when driving is safe for patients with Alzheimer’s disease involves a nuanced professional assessment. For families like the Collinses, technology offers a means to support loved ones and a sense of normalcy and independence as long as safely possible.