People living with cognitive impairment often are able to make their decisions independently. But as their condition changes, their decision-making abilities change as well.

How should people living with mild cognitive impairment or mild stage dementia, their families, and physicians navigate this typically slow and difficult transition? Is there some livable space between what seems to be two extremes — either to try one’s best or surrender and let others take over?

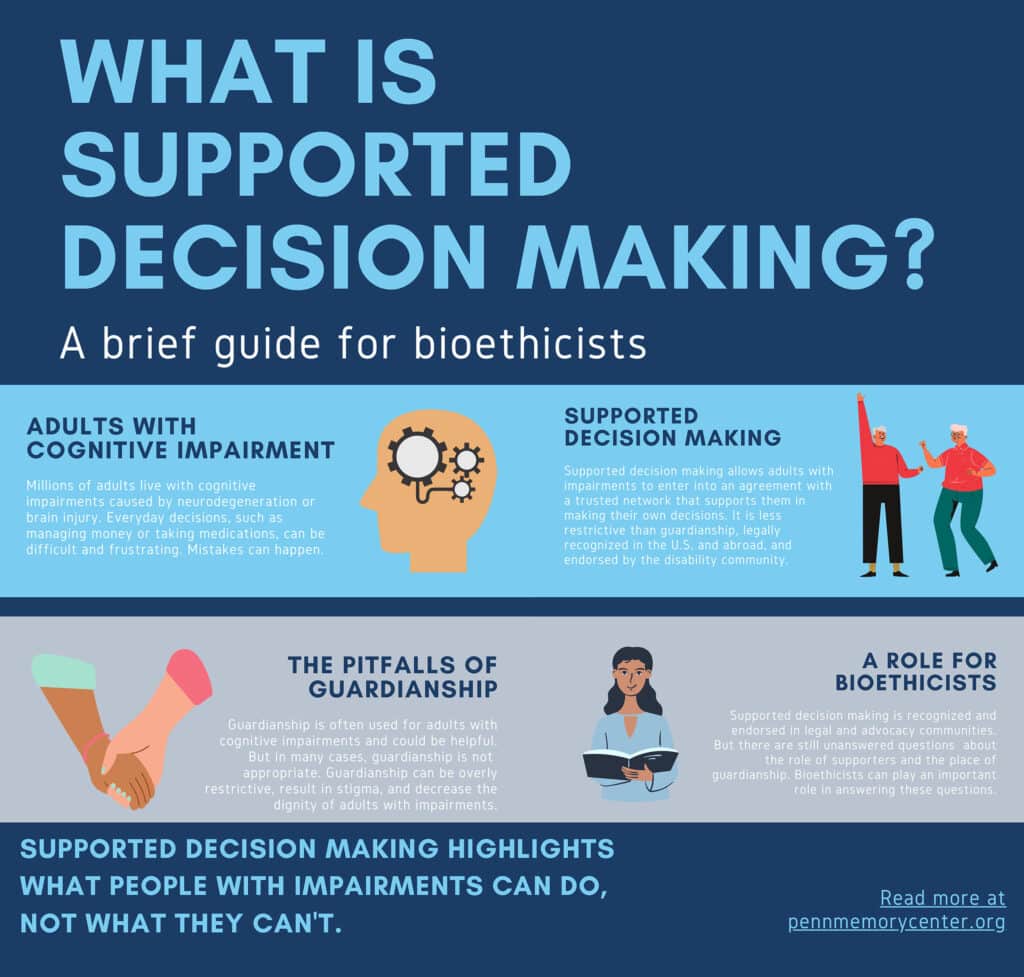

Supported decision making offers a third way to approach this issue. Supported decision making allows people with impaired decisional abilities to retain their decision-making independence by choosing friends and family members who help them make choices rather than make the choices for them. Supported decision making focuses on what people with cognitive problems can do—with the provision of support. This is in contrast with other legal frameworks, like guardianship, which are designed to restrict a person’s decision-making independence.

What is supported decision making?

Supported decision making is a process by which somebody who has cognitive impairment finds a trusted other or network of others who can help them make their own decisions. This process promotes the autonomy and dignity of individuals with Alzheimer’s and related dementias and prolongs the period where people can make decisions for themselves.

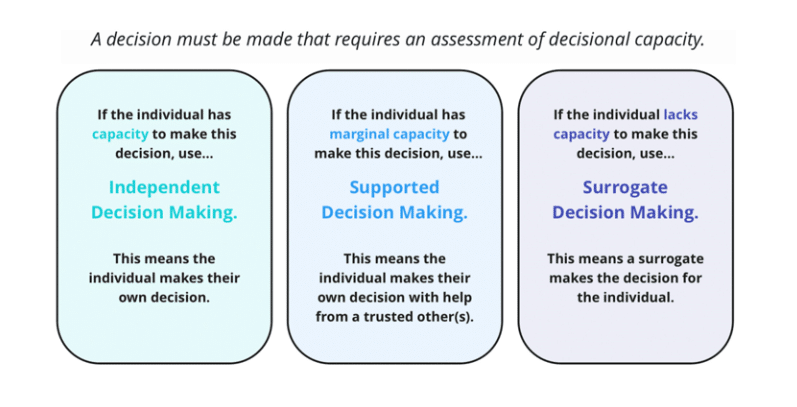

There are several categories of decision-making capacity. When an individual has full decision-making capacity, they make their own decisions. When an individual lacks capacity, a surrogate will make decisions for the individual. Marginal capacity describes individuals with some inefficiencies in decision-making. If an individual has marginal capacity, supported decision making can be used to make the decision.

More on supported decision making

An Instrument Heard Round the World: How the Assessment of Capacity for Everyday Decision-making, or ACED, launched a revolution in the elder care

Jason Karlawish, MD, and James Lai, MD, set out to develop a tool to measure capacity of everyday decision-making. Read article from Penn Memory Center.

“Britney Spears didn’t feel like she could live ‘a full life.’ There’s another way.”

Supported decision-making is a promising alternative to guardianship — even Democrats and Republicans can agree on this. “Making your own decisions is at the heart of what it means to be a person,” wrote Emily Largent, JD, PhD, RN; Jason Karlawish, MD; and Andrew Peterson, PhD. Read article in New York Times.

Baruch A. Brody Lecture in Bioethics on Supported Decision Making by Emily Largent

Emily Largent, JD, PhD, RN, was awarded the 2023 Baruch A. Brody Award for her research on supported decision making as cognition declines. Watch her lecture on this groundbreaking work.

Supported decision making: Facilitating the self-determination of persons living with Alzheimer’s and related diseases

Emily Largent, JD, PhD, RN; Andrew Peterson, PhD; and Jason Karlawish, MD, describe supported decision making, discuss its ethical and legal foundations, and identify steps by which geriatricians can incorporate it into their practice. Read article in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

My brother’s recovery from a car crash became a lesson in how to talk to doctors and nurses

Emily Largent, JD, PhD, RN, recounts lessons learned about patient-doctor communications and decision making after her brother was injured in an accident. Read article in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Pa. Supreme Court Advisory Council hosts first Guardianship Justice Summit

The first Pennsylvania Guardianship Justice Summit was held on Sept. 20-22, 2023, and was hosted by the Office of Elder Justice in the Courts (OEJC) and Advisory Council on Elder Justice in the Courts. A main topic of the summit included promoting alternatives to guardianship. Read a recap of the summit.

Contact

For more information on supported decision making, please reach out to Emily Largent at elargent@pennmedicine.upenn.edu or Jason Karlawish at jason.karlawish@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.