By Meghan McCarthy

Rose looks down at a stack of bills on her kitchen counter and bottles of prescriptions besides them. The bills need to be paid. The pills, organized.

A month ago, the sight would cause immediate overwhelm for Rose. After her diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) earlier in the year, managing such tasks has become increasingly difficult.

Yet Rose doesn’t feel overwhelmed. After her diagnosis, Rose recognized that she needed more familial support. It was then that her clinician first taught her about supported decision making.

Just a month earlier, she and her niece developed a supported decision-making agreement. In it, they specified that Rose’s daughter would spend the first Saturday of the month helping pay bills and organize medications.

Supported decision making is a process by which somebody who has cognitive impairment finds a trusted other or network of others who can help them make their own decisions.

A supported decision-making agreement, like the one between Rose and her niece, is a customizable agreement between a deciding individual and their supporter. The document can specify support in areas ranging from personal care and money to health choices and work arrangements. It can be provided to third parties, such as the patient’s doctors, lawyer, or financial managers.

For individuals like Rose, or those with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias (ADRDs), there will come a time when an individual’s capacity to make decisions declines or becomes limited.

At the Penn Memory Center (PMC), decision making capacity and the ability to support loved ones as this capacity changes is at the heart of the work done by Emily Largent, PhD, JD, RN, Jason Karlawish, MD, and Andrew Peterson, PhD. Their collaboration is a blend of skills in law, public policy, ethics, dementia care and the philosophy of mind.

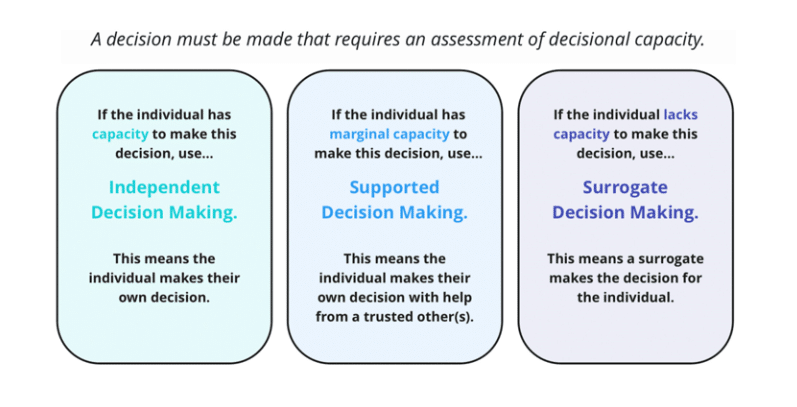

Often, it’s thought that capacity exists as one point on a binary. Either an individual has full capacity and can make their own decisions, or an individual lacks capacity and needs a surrogate to make their decisions for them. The PMC team refutes this point.

Marginal capacity describes individuals with some inefficiencies in decision making. Perhaps it is more challenging for them to weigh pros and cons or keep multiple facts in mind at one time.

For example, someone with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), may fit this category.

“They may be a little bit more prone to errors or have a slower decision-making process,” said Dr. Largent. “But, with the provision of support from another person, that they are able to make their own decisions, and they can make better decisions with that help.”

In their most recent publication, in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, the PMC team explores how to best aid individuals with marginal capacity.

The answer, they believe, lies in supported decision making.

Ideally, individuals have a network of supports to aid in their decisions.

“This network is a way to personalize the process,” said Dr. Largent, “because it allows multiple perspectives from the people best suited to help with different types of decisions.” For example, one family member may be best-suited to help with finances while another may be best-suited to help with managing medical care.

This process promotes the autonomy and dignity of individuals with ADRDs and prolongs the period where people can make decisions for themselves.

For those practicing it, supported decision making is individualized.

“It’s incredibly flexible,” said Dr. Largent. “The person who needs support and the people supporting them can work together to identify particularly challenging areas where help will be most useful.” Moreover, supported decision-making agreements can be changed over time.

This process is often intuitive for those close to their loved ones, and many individuals naturally incorporate supported decision making practices into their daily lives. Yet, there can be benefits to having supported decision making agreements recognized by law.

Numerous states have laws recognizing supported decision making.

“The value of supported decision making increases when others – like a doctor, banker, or lawyer – are willing to recognize the decision making,” said Dr. Largent. “A law can allow third parties to trust and honor decisions made by the individual with help from their supporter.”

While the implications vary depending on state law, legal recognition is also an important step in making supported making a true alternative to guardianship.

In recent years, guardianship and conservatorship became prominent press topics in light of Britney Spears’ legal case. The singer, who was under her father’s conservatorship since 2008, had no legal authority to make either personal or professional decisions. While the California court originally placed Spears under permanent (lifelong) conservatorship, she successfully petitioned for its termination in 2021.

Although supported decision making is an alternative to guardianship and conservatorship, Spears’ case highlights the importance of its state recognition. To be a true alternative, it must be recognized in court.

Spears’ case drew attention to guardianship and how it strips people of rights to make decisions about their own lives. While some people need a guardian, others do not and will benefit from less restrictive alternatives – alternatives like supported decision making.

The article defines how clinicians, specifically, can respect and honor supported decision making in their practice.

Dr. Karlawish sees substantial advantages to supported decision making for the care of persons with Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy Body disease and other diseases that can impair capacity.

“As a clinician, supported decision making is smart, ethical way to negotiate assistance. The key is to have a person who is available, reliable and trustworthy,” he said. “Sure, this is often obvious – a spouse or adult child. Not all patients have these kinds of networks, and, even if they do, some people may be more available, reliable and trustworthy.”

This starts with clinicians introducing the concept of supported decision making to patients and families. They can then facilitate the supported decision-making process by ensuring there is a chair for the supporter to sit in during an appointment, sharing information with both the supporter and patient, and recording who the supporter is in a patient’s chart to ensure they’re involved in future decisions.

Ultimately, supported decision making is a fluid process. As Alzheimer’s symptoms progress, the decision-making capacity of an individual may change, thus changing the kind of support needed.

“Cognition and function will change over time in patients with neurodegenerative diseases,” said Dr. Largent. “We’re working to understand transition points and how clinicians and caregivers can continue to best support their loved ones throughout the process.”

To learn more about the legality of supported decision making, please click here.

For resources about supported decision making through the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), please click here.

For more information on SDM work at PMC, please click here.

If you are interested in creating a supported-decision making agreement, please click here.