Anti-amyloid treatment for Alzheimer’s disease has recently entered clinical use. The ability of anti-amyloid drugs to slow the progression of dementia is unprecedented. However, it is unknown how patients and their caregivers value a delayed course of cognitive impairment and how they weigh its significance against the burdens posed by anti-amyloid treatment. In this study, we are interviewing and observing patients, caregivers, and clinicians as they make decisions about anti-amyloid treatment and interpret its effects. We will use our findings to advance the ethical usage of anti-amyloid drugs and inform how clinicians communicate about these drugs with patients and families.

STEP-UP, Recruitment into Alzheimer’s disease registries

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) recruitment registries are common tools for accelerating enrollment into AD prevention trials, but registry enrollees are predominantly female and white. This perpetuates the lack of diversity among AD prevention trials participants. The STEP-UP project seeks to understand how to effectively communicate the importance of participating in AD prevention studies to men and minorities. Effective communication can result in increased enrollment of men and minorities into AD recruitment registries and greater diversity among AD prevention study participants. To accomplish these objectives, researchers are

- identifying the psychosocial determinants for joining different AD recruitment registries

- assessing how these determinants vary by race/ethnicity and gender

- developing evidence-based, culturally relevant recruitment messages based on these findings

- deploying the evidence-based messages into a real-word testing environment and measure their impact on enrollment of men and minorities

Dementia detection in primary care

Cognitive impairment, including dementia, often goes undetected. Early detection of cognitive impairment is important because it enables patients and their families to access appropriate care supports and research opportunities. The majority of patients seeking evaluation of cognitive symptoms begin their diagnostic journey in primary care, but it is particularly challenging to detect cognitive impairment in primary care due to a number of factors. This study aims to understand the barriers to detection of cognitive impairment in Penn Medicine primary care practices. This information will be used to design an intervention to improve the quality of evaluations for cognitive impairment at Penn Medicine.

Plasma AD biomarkers

New diagnostic tests for Alzheimer’s disease are rapidly becoming available, but there is little information on how these tests will impact clinical practice. This project aims to understand clinician perspectives on use of blood-based, or plasma, tests for markers of Alzheimer’s disease and determine how these tests might impact patient care. We aim to identify factors that may influence use of these tests in clinical care and determine in which medical specialties (such as primary care, neurology, or geriatrics) they may be used. Additionally, we will assess how plasma Alzheimer’s disease biomarker results might impact aspects of patient care, such as disclosure of a diagnosis and medical management. Understanding how these tests might be used will inform efforts to translate these tests into clinical practice.

Social and Structural Determinants of Health (SSDoH)

Research shows that people have different experiences, opportunities, and challenges depending on their background and life circumstances. These factors can be important social and structural determinants of health (SSDoH) that may help explain heterogeneity in cognitive, functional, and interventional outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs). The National Institute on Aging (NIA) has set as a priority collecting SSDoH data. The Penn Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) is working to routinely collect measures via a REDCap survey that asks questions about childhood, adulthood, and current living status. This information may help elucidate disease mechanisms and modifiers as well as aid discovery of disease modifying treatments that are effective across socioculturally diverse populations.

Establishing a Framework for Gathering Structural and Social Determinants of Health in Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers (The Gerontologist)

From 5 to 95: The Impact of Life Experiences on Brain Health (Penn Memory Center)

Principle investigator: Shana Stites

Caregivers’ Experiences with and Perspectives on Communication with Persons with Dementia

The Caregivers’ Experiences with and Perspectives on Communication with Persons with Dementia study examines how people with dementia and their caregivers communicate with one another in the late stages of the disease. We seek to systematically describe this communication and how it affects caregivers’ clinical and daily care decisions. Discovering how this communication unfolds can better prepare clinicians to respond to certain caregiving concerns and issues.

Principle investigators: Jason Karlawish, Andrew Peterson

COVID Caregiving

The current COVID-19 pandemic presents unique circumstances for persons living with dementia and their care partners. This project aims to characterize the practical, emotional, social, and behavioral effects of COVID-19 on care partners and persons with dementia; to compare the experiences of care partners when the person living with dementia resides in the home versus in a long-term care setting; and to document changes over time.

Research on this subject is important because it may expose vulnerabilities and flaws in existing systems for persons living with dementia and their care partners and offer insights into interventions that can improve or protect quality of life during times of non-emergency. Additionally, it may inform pandemic and emergency preparedness going forward.

Impact of biomarker result disclosure on family and friends: REVEAL SCAN Study Partner Study

Impact of biomarker result disclosure on family and friends: REVEAL SCAN Study Partner Study

The discovery of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers is transforming our understanding of AD to include a “preclinical” stage of AD in which individuals are cognitively and functionally unimpaired but have biomarkers that correlate with increased risk for developing AD dementia. At present, there is ongoing debate about the practical and ethical aspects of biomarker disclosure in the preclinical stage. Discussions typically focus on the effect on the cognitively unimpaired but at-risk individual. It is also essential, however, to understand how biomarker disclosure affects the at-risk individual’s family and friends. P3MB is gathering and analyzing data to see how biomarker disclosure affects participants and their study partners.

Emily A. Largent & Jason Karlawish, Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease and the Dawn of the Pre-Caregiver, JAMA Neurology, doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0165 (2019).

Reactions to gene and biomarker results: The SOKRATES Studies

Reactions to gene and biomarker results: The SOKRATES Studies

As Alzheimer’s disease (AD) secondary prevention trials require participants to undergo genetic or biomarker testing in order to enroll, researchers must address how to disclose the results of tests that foreshadow whether a healthy person may develop AD dementia as well as the implications of these disclosures. As interventions to prevent or delay symptoms move from research to clinical practice, so will these challenges surrounding disclosure.

Through research that includes the SOKRATES 1 (Study of Knowledge and Reactions to Amyloid TESting) and SOKRATES 2 (Study of Knowledge and Reactions to APOE TESting) studies, P3MB researchers are collecting data to understand the experiences of cognitively unimpaired individuals who learn the results of AD gene and biomarker tests. Topics explored include individuals’ emotional reactions to these results, including any psychological or emotional challenges, any changes in their relationships and sense of self, their health behaviors, and how they are thinking about and planning for the future.

To learn more about what we’re discovering:

Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, et al. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alz Res Ther. 2015;7:26.

Mozersky J, Sankar P, Harkins K, Hachey S, Karlawish J. Comprehension of an elevated amyloid positron emission tomography biomarker result by cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(1):44-50.

Harkins K. & Karlawish J. Disclosing amyloid status to a person without cognitive impairments: Anticipating a novel clinical practice. Practical Neurology, June 2018. http://practicalneurology.com/2018/06/disclosing-amyloid-status-to-a-person-without-cognitive-impairments/

Grill JD, Cox CG, Harkins K, Karlawish J. Reactions to learning a “not elevated” amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018 Dec 22;10(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0452-1.

The Stigma of Alzheimer’s Disease

Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease

The stigma of Alzheimer’s disease has notable impacts on patients, their families and society. It leads to lower quality of life of persons with dementia, can spillover to worsen health outcomes of caregivers and can discourage individuals from seeking appropriate care and participating in research. P3MB is gathering and analyzing data from varied sources to understand mechanisms of how stigma effects persons in varying stages of cognitive decline and how stigma associated with clinical stages of disease does or does not spill over to affect cognitively unimpaired people who learn they are at risk for Alzheimer’s disease through gene and biomarker testing.

To learn more about what we’re discovering:

Stites SD, Karlawish J, Harkins K, Rubright JD, Wolk D.: Awareness of Mild Cognitive Impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia diagnoses associated with lower self-ratings of quality of life in older adults. The Journal of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 72(6): 974-985, Oct 2017.

Stites SD, Johnson R, Harkins K, Sankar P, Xie D, Karlawish J.: Identifiable characteristics and potentially malleable beliefs predict stigmatizing attributions toward persons with Alzheimer’s disease dementia: Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Health Communication 33(3): 264-273, Mar 2018. PMCID: PMC5898816

Stites SD, Rubright JD, Karlawish J.: What features of stigma do the public most commonly attribute to Alzheimer’s disease dementia? Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 14(7): 925-932, Mar 2018.

Stites SD, Harkins K, Rubright J, Karlawish J: Relationships between cognitive complaints and quality of life in older adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment, mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia, and normal cognition. Alzheimer’s Disease & Associated Disorders Page: 276, 2018 Notes: doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000262.

Stites SD, Rubright JD, Harkins K, Wolk D, Karlawish J.: Awareness of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia diagnoses associated with decreased self-ratings of quality of life in older adults. Alzheimers Dementia 14(7): 599-600, 2018 Notes: doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.681

Stites SD.: Cognitively healthy individuals want to know their risk for Alzheimer’s disease: What should we do? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 62(2): 499-502, 2018.

Stites SD, Milne R, Karlawish J.: Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.02.006 10: 285-300, 2018.

Stites SD & Karlawish J.: Stigma of Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia: Considerations for Practice. Practical Neurology Jul 2018 Notes: http://practicalneurology.com/2018/06/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia/

Barriers to research participation: Study Partner Availability Limitations Study

Barriers to research participation: Study Partner Availability Limitations Study (PALS)

Study partners are essential to assuring the scientific validity and social value of preclinical AD research. The participant-study partner pairing is known as a “dyad.” Study partners report on participants’ cognitive status, which serves two important purposes. First, before enrollment, study partners assist investigators in establishing that participants are eligible to enroll. Second, post-enrollment, study partners provide information to evaluate the experimental intervention’s efficacy. Although it is conceivable to design AD trials that don’t require dyads, there would be significant limitations of such trials. To successfully engage broad segments of the American public in preclinical AD research, we must understand and address the disparate effects of the study partner requirement on trial participation and representativeness. P3MB is collecting data to understand barriers to the identification and engagement of study partners in research and to identify promising means of reducing these barriers.

Emily A. Largent, Jason Karlawish, Joshua D. Grill, Study Partners: Essential Collaborators in Discovering Treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy, doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0425-4 (2018).

Whealthcare

Whealthcare

The inability to continue managing one’s finances is one of the earliest signs of cognitive decline in an aging brain. This intersection between brain health and wealth is what P3MB Director Jason Karlawish describes as Whealthcare. These changes in financial capacity may lead to errors, bad decisions, fraud, or abuse among older adults, who are often already experiencing a loss of wealth during retirement. To address this junction, Dr. Karlawish and his team are working with banking and financial industries to develop strategies to protect elder financial management and prevent abuse. Bank and financial partners are seen as instrumental partners in providing cognitive screening, financial monitoring, and education and empowerment to older adults. Whealthcare aims to bring together healthcare teams and financial institutions to make this partnership happen.

Typical Day Photo Elictation Study

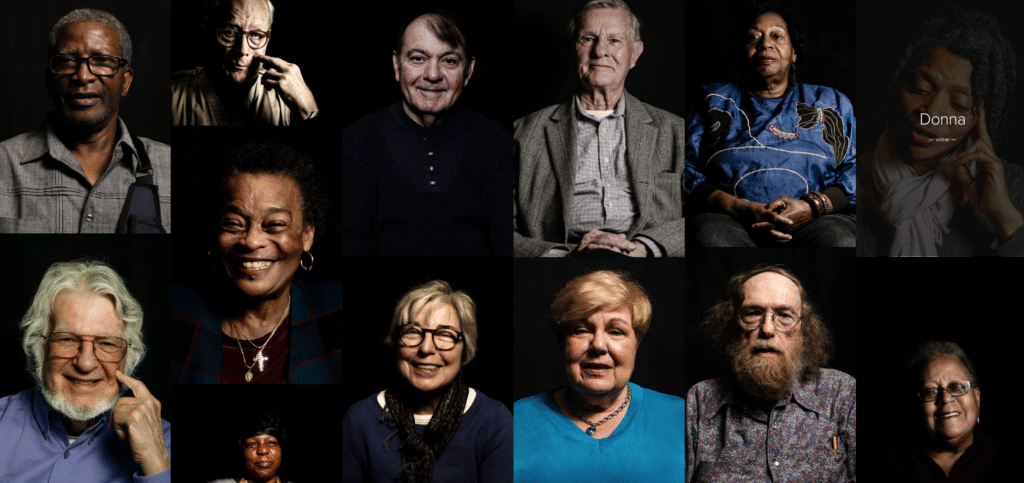

Typical Day

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is much more than a condition in which people have more memory or thinking problems than normal for their age. For some, MCI may mean lifestyle or hobby changes, while for others it may mean a heavier reliance on current routines. Either way, MCI is a personal experience that is much larger than the original diagnosis from a doctor. People can learn a lot from others just by asking the question “what’s a typical day?”

“Typical Day,” founded by Tigist Hailu, MPH, is a photography project that allows older adults living with MCI to document and communicate their lives after their diagnosis. Through photography and stories, Hailu hoped her work would add more humanity into how people think about dementia. Often challenging to portray through words, the people featured in this project show readers their world through photography of people, places, and objects that define their daily lives. These photos serve as a tool to facilitate conversations with researchers and community members as a way to raise awareness of cognitive impairment.

Who is eligible for brain donation to our program?

Patients, normal controls, and other research participants who have been well evaluated over time by the Penn Memory Center.

How is the brain donation procedure performed?

The brain is removed by experienced autopsy technicians through an opening created low on the back of the skull. All other tissue is then properly repositioned and carefully sewn in place, with the stitches hidden. There are no visible indications of the procedure, should open casket viewing be desired.

Are funeral arrangements affected, or are there costs involved?

No. The next-of-kin of the registered brain donor simply contacts our autopsy telephone service, operating 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and holidays, immediately after the registered donor’s death. Our service pays your designated funeral provider for transport of the body to the University of Pennsylvania for the brain donation procedure, which requires approximately two hours to perform, and to then transport the body to your funeral facility. There is no charge to a family for any aspect of the brain donation process.

How is donated brain tissue used?

The brain is examined by neuropathologists at Penn’s Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR), and the donor’s family receives a report. Tissue is used in current research and banked for future study. Samples may also be shared with researchers worldwide who can add to and advance our knowledge.

Is donation compatible with religious beliefs?

Organ and tissue donation, for medical diagnosis and to advance research that can help provide a healthier future for generations to come, is compatible with nearly all world religions. If you have concerns, please discuss this issue with your spiritual advisor to learn how your religion interprets brain donation.