By Meghan McCarthy

Caregiving is an essential element to the safety and wellbeing of individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). Yet, little has been done to understand the diverse experiences of caregivers who inevitably have different lives and identities.

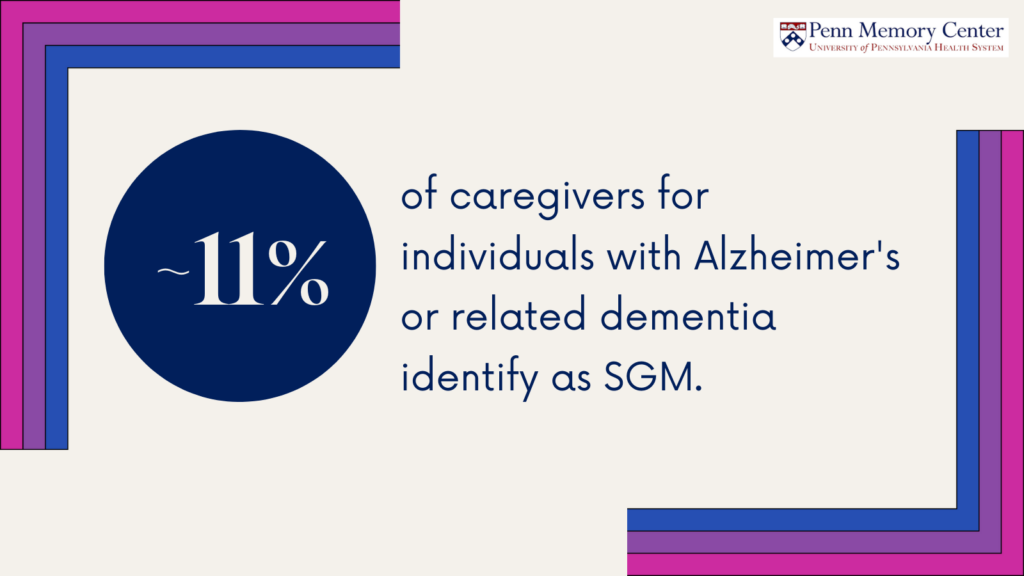

Although there isn’t nationally representative data, an estimated 11 percent of ADRD caregivers identify as sex and gender minorities (SGM).

Krystal Kittle, PhD, is a visiting research assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in the school of public health, social and behavioral health department. Dr. Kittle’s current research focuses on caregiving experiences, health, and wellbeing of racial/ethnically diverse SGM ADRD caregivers.

Dr. Kittle is dedicating her current research to fill this gap.

While caregiving has inherent challenges, Dr. Kittle’s research has found that SGM caregivers face unique obstacles.

“They may be caring for someone who does not accept their identity, which is most prevalent amongst adult children taking care of their parents,” said Dr. Kittle.

For example, a caregiver who identifies as transgender may face bias and discrimination from their parent whom they are caring for. They then face a conflict: responsibility to care for oneself versus the responsibility to care for their parent.

Greater research is needed to fully understand these nuanced experiences.

To start, Dr. Kittle’s current research focuses on uncovering specific demographics of SGM caregivers.

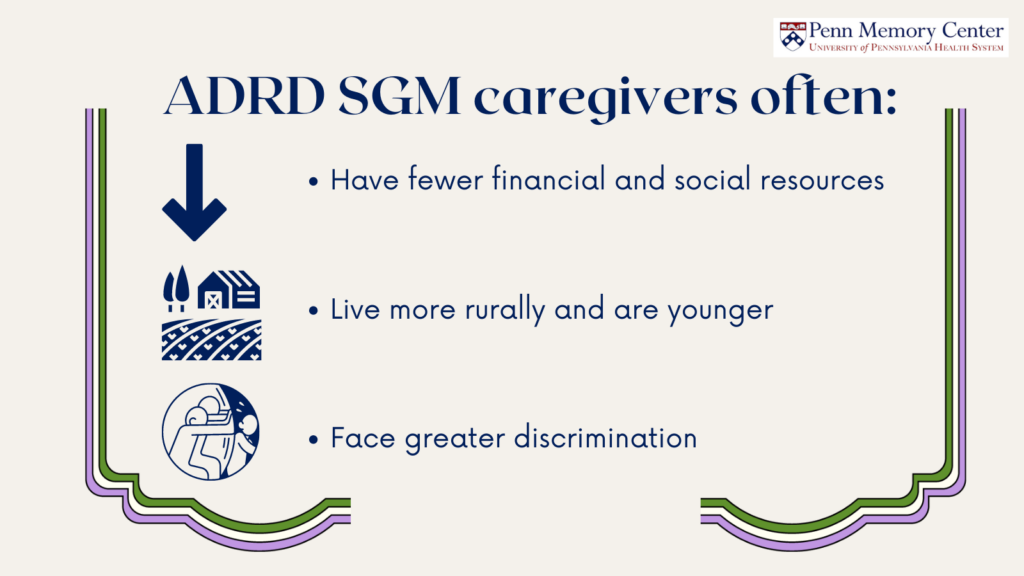

Currently, data suggests that SGM caregivers are equally likely to identify as male or female, unlike non-SGM caregivers, who most often are women. On average, SGM caregivers are also younger and live more rurally than non-SGM caregivers. SGM caregivers also have fewer financial and social resources compared to non SGM caregivers.

While researchers have theories on reasons for these differences amongst demographics, there isn’t concrete data to support them yet.

Providers are more likely to ask ADRD SGM caregivers if they need help with caregiving. However, data shows that SGM caregivers are less likely to use respite or transportation services.

In one study by Joel Anderson, PhD, CHTP, FGSA, mental health and caregiving experiences within SGM subgroups was examined. Results showed that without support, SGM caregivers face major disparities within their own health and wellbeing. Below are key findings:

- 1/3 of the sample had below average health status. This disparity was greatest amongst transgender and lesbian participants.

- SGM individuals reported more discrimination, victimization, and microaggression than others.

- Many reported moderate to high levels of stress, and/or probable depression.

- SGM caregivers of color have lower quality of life than white SGM caregivers.

“There are explicit mental health challenges that need to be addressed within support interventions,” said Dr. Kittle. “Challenges are often a result of the intersection between challenges associated with being SGM, such as stigma and discrimination, and challenges associated with being a dementia caregiver.”

Like most caregivers, SGM individuals can find their role overwhelming. Yet, unlike non-SGM individuals, they often find support resources unapproachable.

“When SGM caregivers go to caregiving support groups, they often feel very uncomfortable from the start,” said Dr. Kittle.

Kittle suggests considering an example of a caregiver who is lesbian and takes care of her partner. If group facilitators frame questions on the assumption that she is taking care of a husband, this language is immediately exclusive.

“She automatically feels isolated. This lesbian-identifying caregiver may fear not being accepted by the group from the get-go, and uncomfortable correcting the language used,” said Dr. Kittle.

While greater research is needed to know the full extent of SGM caregiving experiences, Dr. Kittle advocates for intervention measures that create a safe space for all.

Changes can be as simple as referring to spouses as partners instead of assuming husband-and-wife.

Having support groups that are specific to SGM identifying individuals, and even subgroups, such as bisexual caregivers, would also improve SGM caregiver’s sense of community and comfort.

Within the clinical space, creating an environment of holistic care begins with physicians having knowledge about the SGM experience.

Tying back to research needs, an understanding of SGM caregiver demographics is crucial to providing supportive care. It’s also important to acknowledge that, like non-SGM caregivers, SGM caregivers also experience many positive aspects to their role.

“The goal is to have caregivers feel welcome and comfortable speaking freely, without fear or shame, to their clinicians,” said Dr. Kittle.

If you or someone you know identifies as an SGM caregiver, Dr. Kittle is currently enrolling participants for multiple studies.