By Meghan McCarthy

Editor’s Note: This article is part of the Disability and Dementia Series, an ongoing project highlighting the experiences of individuals with intellectual disabilities who are affected by Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs).

Why do some individuals develop Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs) while others do not?

Cognitive resilience and resistance offer promising lens for understanding this complexity. This dual phenomenon is at the heart of ongoing research led by Rory Boyle, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center (FTD) Center. Along with an international team of colleagues, Dr. Boyle is working to develop a framework for understanding resilience and resistance in Alzheimer’s disease associated with Down syndrome (DSAD).

Currently 1 in 9 people aged 65 and older in the general population is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In comparison, it is estimated that over 50% of adults with Down syndrome (DS) are affected.

This disparity is believed to be largely due to genetics. Individuals with DS have a third copy of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, which increases their risk of amyloid buildup in the brain—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

However, some individuals with DS who show changes in their brain consistent with ADRDs—such as amyloid and tau accumulation—do not exhibit symptoms of dementia during their lifetime. Analyzing data from the brain bank at the University of California Irvine (UCI) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Dr. Boyle and his team found that about 13% of cases examined did not present with dementia symptoms, despite neuropathological findings indicative of an AD diagnosis.

This week, Dr. Boyle’s team published a manuscript providing a framework for future research on this discrepancy.

“It’s a simple demonstration of the fact that these individuals were resilient to the effects of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” Dr. Boyle said. “That inspired our review paper: we’re trying to understand how we can study resilience in the context of Down syndrome.”

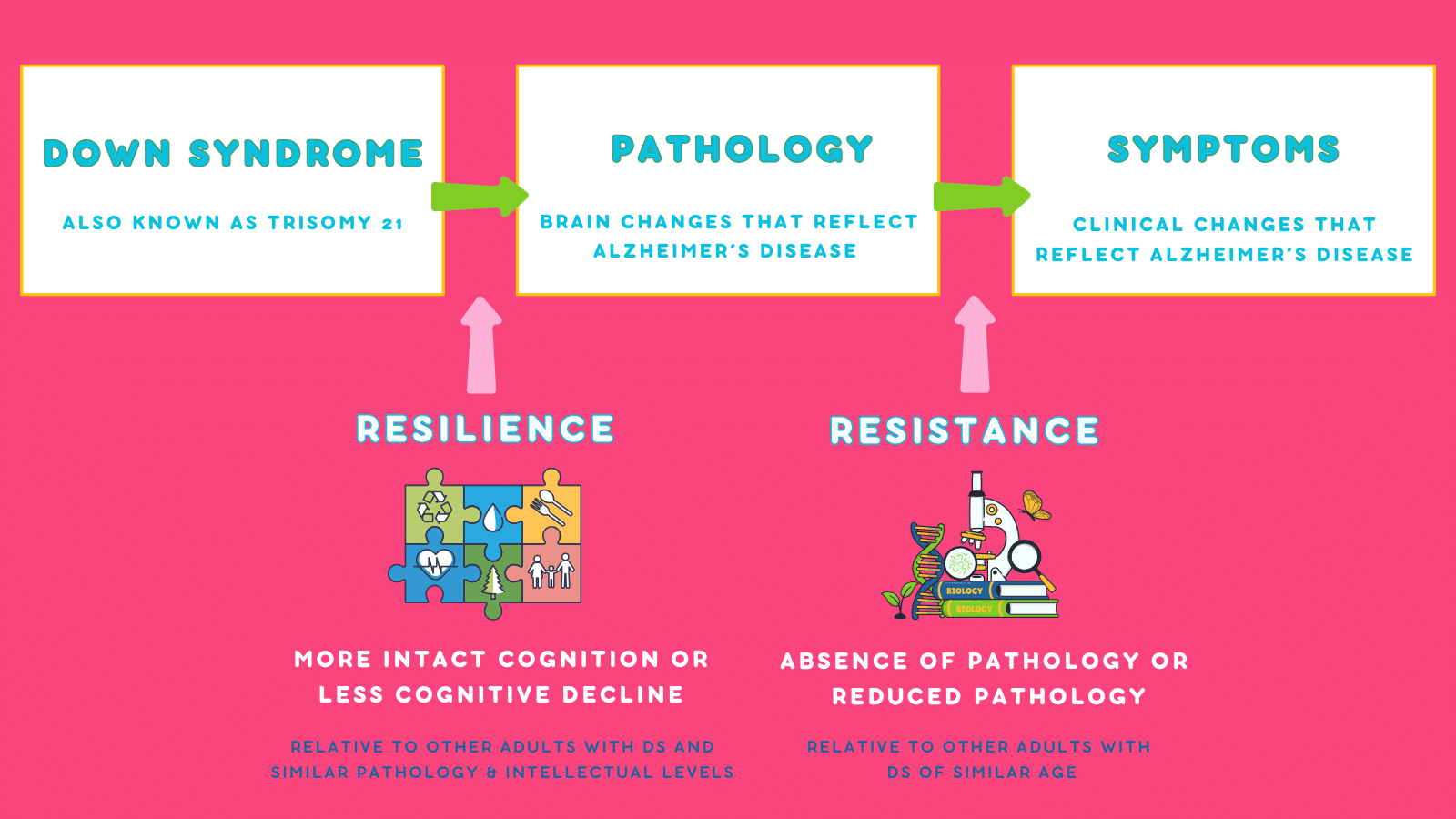

Resilience and resistance

Cognitive resilience refers to the brain’s ability to maintain function and health despite neuropathological changes, often shaped by environmental and social factors. In contrast, cognitive resistance operates on an individual and biological level, such as genetic predisposition, to mitigate cognitive decline. Together, resilience and resistance may explain why some individuals, including those with DS, exhibit Alzheimer’s pathology in brain tissue but do not develop dementia symptoms.

“We wanted to put together a framework for researchers to effectively and methodologically study the factors that might be associated with resilience and resistance to AD in Down syndrome,” Dr. Boyle explained.

To begin, the research team refined the definitions of resilience and resistance to better incorporate individuals with DSAD.

Resistance: Defined as lower-than-expected levels of Alzheimer’s pathology, compared to other individuals with DS of the same age.

Resilience: Defined as better-than-expected cognitive performance given a certain level of Alzheimer’s pathology, compared to age-matched peers with DS.

Developing a framework

To create their framework, the team reviewed existing evidence of resilience and resistance in DSAD. Specifically, they examined timing differences in biomarker (amyloid and tau) accumulation, symptom onset, and cognitive impairment.

“People are paying more attention to inequities in social and structural determinants of health and how these give rise to disparities in dementia outcomes,” Dr. Boyle said. “These also exist for people with Down syndrome.”

The team identified several factors that might influence resilience and resistance. For resilience, they examined the role of social determinants of health, such as lifestyle and environmental factors. For resistance, they focused on biological factors, including genetics and sex differences among individuals with DSAD.

Beyond ADRDs, individuals with DS are at higher risk for several other health conditions such as blood disorders, epilepsy, and congenital heart anomalies. Dr. Boyle and his team considered the relationship between coexisting conditions and resilience and resistance factors. For example, approximately 80% of adults with DS have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) compared to 26% of general adult populations. Current research suggests that sleep quality may be linked to greater cognitive resilience in people without DS.

“We wanted to evaluate the most promising targets and factors that could promote resilience and resistance to DSAD,” Dr. Boyle stated.

Looking ahead

Several global studies such as the Horizon21 Consortium and Alzheimer Biomarkers Consortium- Down Syndrome (ABC-DS) aim to better understand DSAD.

For instance, the ABC-DS study has found that elevated and abnormal levels of amyloid become evident in the brain, on average, at age 35 for individuals with DS. Those who don’t show AD biomarkers, such as tau and amyloid accumulation, demonstrate resistance to the disease.

Dr. Boyle’s team hopes their framework will help researchers better assess and understand resilience and resistance in DSAD. Additionally, they also aim to inspire changes in healthcare policy and research priorities to improve outcomes for individuals with DS.

“If the field can work towards identifying factors associated with delayed accumulation and promote these at a population level, we can work towards better outcomes for people with Down syndrome,” Dr. Boyle stated. “I think this is as much a research framework as it is a call to action.”

To read Dr. Boyle’s full manuscript, please click here.