Editor’s Note: David Ney was a Penn Memory Center communications intern from 2016 to 2017. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 2017 with a degree in biological basis of behavior. He plans to attend medical school next year. This is his reflection on a year with PMC.

By David Ney

When I joined the Penn Memory Center as an editorial assistant, I assumed I would be tracking pharmaceutical companies and research labs to learn about the drugs designed to treat and cure Alzheimer’s disease.

I quickly learned that there is so much more to treating Alzheimer’s disease than can be found on a prescription pad.

PMC offers its patients psychotherapy and Cognitive Fitness classes, and a team of social workers stand ready to advise families on caring for themselves and their loved ones. The PMC team also has a focus on training the next generation of Alzheimer’s disease researchers, making sure that generation reflects the diversity of our nation.

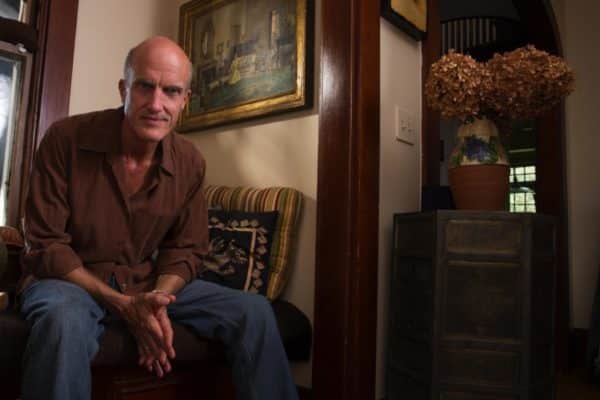

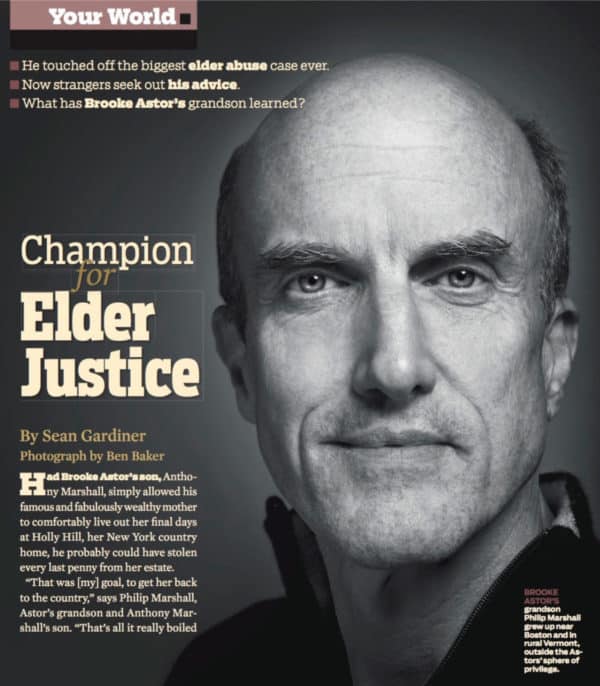

For my part, I wrote about financial scams that target older adults, the importance of study partners in clinical research, how stigma can further hurt those living with Alzheimer’s disease, and about Philip Marshall, a cheery and fascinating professor whose warmth is overwhelmingly contagious.

The more I learned about Marshall’s current work in advocating for elder justice, the more interested I became in his past. As an undergraduate, he double-majored in geology and studio art and spent over his summer hanging around construction sites. Almost haphazardly, he stumbled into a career of historic preservation. This training uniquely positioned him years later to protect and defend his grandmother, Mrs. Brooke Astor, from financial exploitation.

Astor’s work through the Vincent Astor Foundation was responsible for restoring some of New York City’s most prized sites, like the New York Public Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Astor and Marshall both pursued a passion to preserve dignity and beauty in places they valued.

Historic preservation is a fight against entropy, nurturing something old today to keep it around tomorrow. And so together and yet very separately, grandson and grandmother chipped away, pursuing a path of incremental progress.

Then, an event: Marshall discovered that his father, Astor’s son, was financially and psychologically abusing his grandmother. He learned the magnitude of the issue when he visited his grandmother and saw her formerly beautiful home now decrepit and foul-smelling. Astor herself was in poor condition — unable to perform many daily activities, confused by her surroundings. She was in the throes of Alzheimer’s disease and being hurt by her own son.

Then, a choice: Do what is right or do what is easy? What is easy may be to keep quiet, not bother his father, and wait for the trickle-down of inheritance money. But Marshall never considered this an option. His only option, he said, was to rescue his grandmother and to restore her dignity.

The story of this family’s infighting quickly became national news. A quick search yields a seemingly endless stream of palace intrigue about the drawn-out legal battle between father and son over their matriarch. The story received national attention because of the glitzy names involved: Astor, Rockefeller, Kissinger, Reagan, de la Renta. But that is not why I think his story deserves to be told.

Marshall deserves recognition because he saw an injustice, reached out to friends and family for support, and protected his vulnerable grandmother. He is a role model because he did the right thing in those trying moments.

Marshall’s decisions and the steps he took to become an advocate for elder justice are a reflection of intervention-based, in-the-moment treatments embraced by the Penn Memory Center.

As an editorial assistant at the Penn Memory Center, I enjoyed writing about Marshall the Protector and not Marshall, the grandson of Brooke Astor. The former may be less star-studded, but it’s a narrative that embraces impact, progress, and helping those in need. We at the Penn Memory Center focused on the story not because of the celebrity status, but because it was a tragic example of elder abuse followed by the heroic push for elder justice.

When I think of what I value in Marshall’s story, I think of what narratives are important to me in the field of Alzheimer’s disease research: helping those who are vulnerable and alleviating suffering in the present. One narrative we eschew is that there is an upcoming silver-bullet pill for Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, though researchers at PMC are indeed testing different clinical interventions. Instead, we focus on actionable steps for financial institutions and the healthcare industry to protect older adults from financial abuse and scams, what we call Whealthcare. We push away sensationalism to educate and empower those we can help. Articles about daily life and the gritty details of how Alzheimer’s and dementia affects people can make a difference. Stories outlining the damage of stigma may actually decrease the negative impacts of stigma, whereas speculative stories about “silver bullets” provide only false hopes.

It is without doubt that treatments need to be developed to slow and halt the progression of Alzheimer’s, but the Penn Memory Center also fixes its gaze on the problems of today. We focus on the caregivers, study partners, and family members struggling to come to terms with what Alzheimer’s disease means.

With cures not yet in our reach, the focus is on treatments that that can improve health and well-being in the present.

Learn more about Philip Marshall and his ongoing fight for elder justice at www.beyondbrooke.org.