By Danny Yarnall

Michael Duong is expectantly waiting for the final product of his grandfather’s latest work of art: a clock.

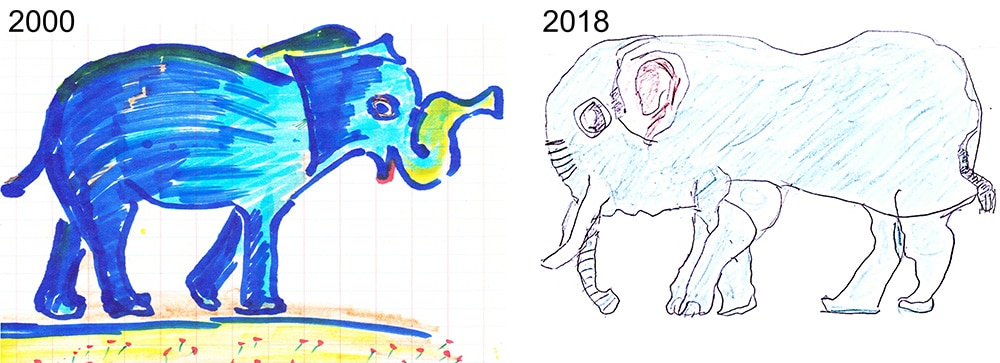

He remembers when he would come home from kindergarten and marvel at the doodles of toys around the house, everyday items or fantastic chimeras and other mish-mashes of animals his grandfather would dream up.

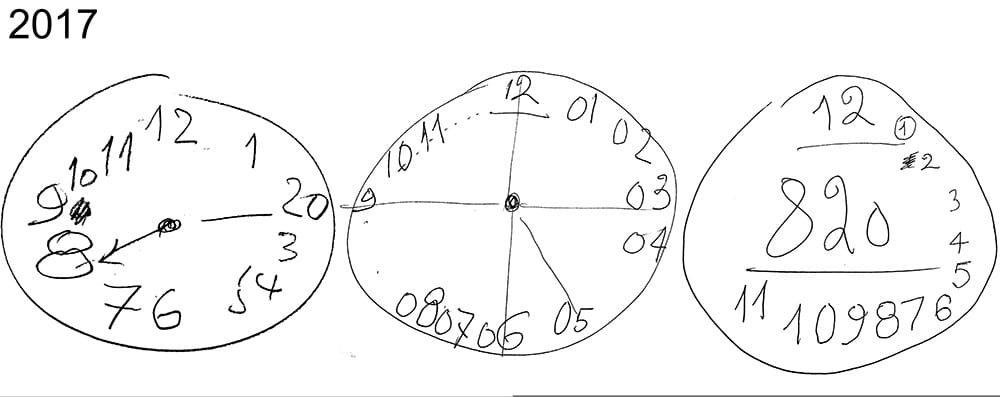

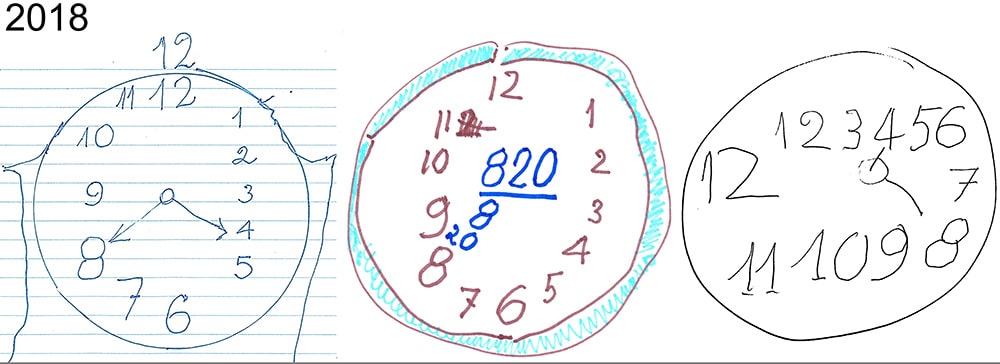

But that was long before his grandfather received an Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Now Michael is administering a simple cognitive test where his grandfather has to draw a clock reading “8:20”.

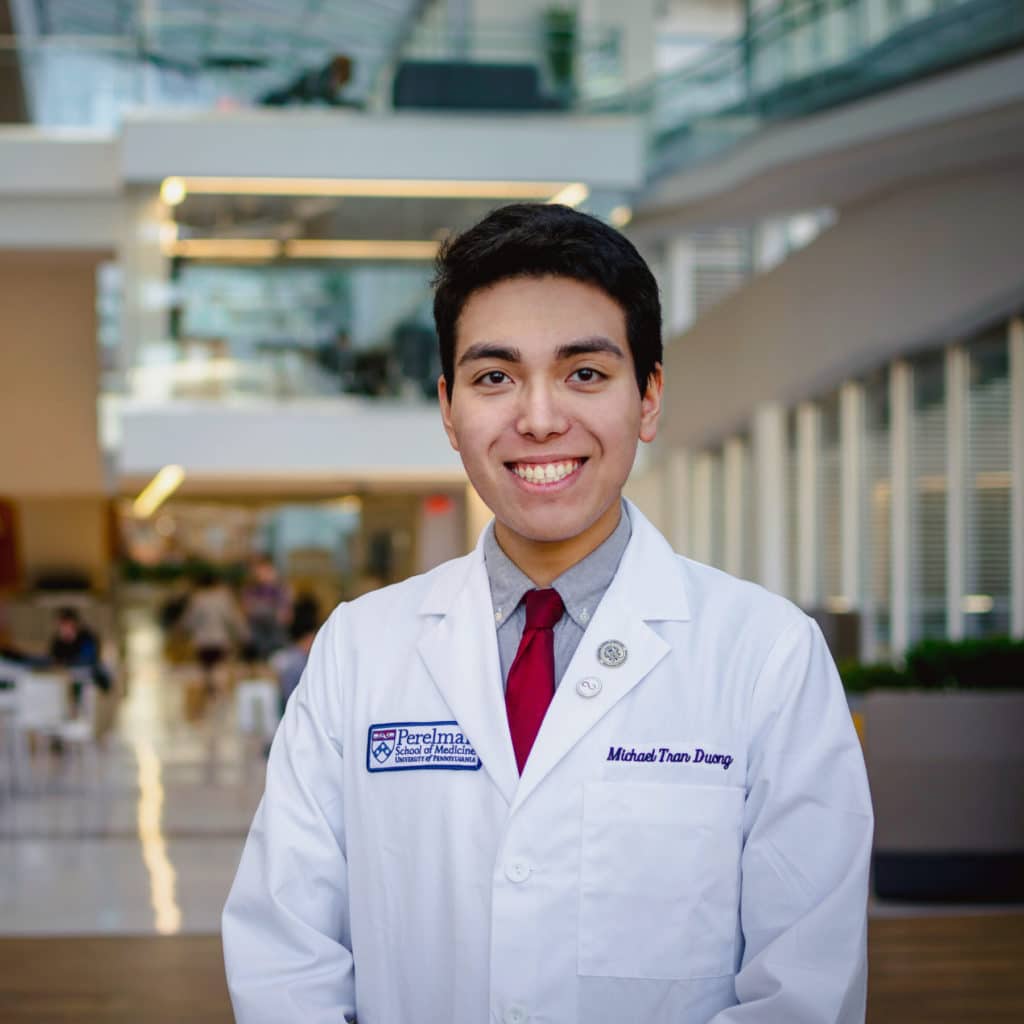

A second-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Michael splits his time between Philadelphia and his Lansdale home where he, his mother, father, and maternal grandparents live after emigrating from Vietnam between the 1970s and late 1980s.

“I found one way to reconnect with him: reprising my role as his personal art appreciator and collector,” Michael wrote in The Art of Caregiving, which appears in August’s edition of JAMA Neurology. His writing on the caregiving experience has also led him to be featured in Science and Penn Today.

He sees the drawings as emblematic of both the caregiver experience as well as the pattern of decline in Alzheimer’s. The clocks vary in detail and accuracy. One sketch from 2018 includes hands and evenly spaced numbers, and while earlier versions just have 8:20 scrawled on the middle of the face.

“It’s not a smooth slope, but more of a roller coaster with highs and lows,” Michael said.

In “The Art of Caregiving”, he outlines that the process of caring for his grandfather was as much about taking care of a loved one as it was learning the very meaning of family, love, and relationships.

“Caregiving is a labor of love. Families give care to loved ones as filial love. Clinicians ease patients’ pain as brotherly and sisterly love,” Michael wrote.

For Michael and his family, even outside of his grandfather’s diagnosis, it has been far from a linear progression to get to where they are now.

During the Vietnam Civil War, Michael’s grandfather was working in the Department of Labor in South Vietnam. His grandfather told him of the chaos and fear around the North Vietnamese invasion that caused many people to flee. His grandfather only had enough money to send his two children, Michael’s mother and uncle, on wooden boats to a small refugee camp on an island outside of Malaysia. They waited for a year on the island until a sponsor family provided them passage to the United States.

“I can’t imagine how it felt for them, leaving their family and home behind, or my grandparents, watching their kids venture into the unknown,” said Michael.

His mother knew Vietnamese and French when she and her brother came to the U.S .and even with a language barrier, she studied well enough in school to get into UPenn for electrical engineering where she met Michael’s father. They found a close-knit Vietnamese community in the area after graduation and eventually saved up enough to bring Michael’s grandparents over in the 1980s.

“That grit from my mother is something I feel I have and inspires me today,” Michael said.

Growing up alongside his grandparents, Michael said the family had noticed common memory slips like lost keys, but the gravity of his grandfather’s situation was truly apparent one winter evening.

Michael had walked into his living room after school one day to find his grandmother alone, the empty cushion next to her was practically reserved for Michael’s grandfather. He felt something was off. When he asked where his grandfather was, his grandmother said he was in the garage working on the car. Michael searched for his grandfather in the garage, only to find the door open and the car missing.

Michael and his family drove around for hours looking for his grandfather. As the hours passed, they called the police.

“It was getting later, and it had snowed the day before. We were all very worried,” Michael said.

Fortunately, they found his grandfather. He was physically alright, but for Michael, the memory underscores the importance of finding a viable treatment for Alzheimer’s.

While watching his grandfather’s progression with Alzheimer’s, Michael dedicated himself to studying neurology and neuroscience, finding answers in and out of the classroom. In addition to enrolling in up to eight classes a semester, he also commuted home to landsdale every evening to help out around the house and care for his grandfather.

One of those classes was a graduate-level course in public health in cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s taught by Memory Center co-director Dr. Jason Karlawish. Michael, then a sophomore, had experience taking higher level courses in his previous semesters and petitioned Dr. Karlawish to attend the class.

“I replied with a cautionary warning about the content but, sure, I said he could enroll,” Dr. Karlawish said, “I’m so pleased I did. Michael was among the most engaged and thoughtful students I’ve taught.”

Michael’s advanced coursework allowed him to finish his undergrad degree in two and a half years. But he had loftier aims than the highest GPA or an expedited path to a career in medicine and public health. For Michael, the main goal was to give his grandfather a chance to watch his grandson graduate.

“Grandpa always stressed how important a college education was. He always held that up and it was important to me that he could be there when I graduate,” said Michael.

However, as the Alzheimer’s progressed, Michael’s grandfather was not able to attend the ceremony but his family made sure to include him in the festivities afterward, Michael noted.

Now as a second-year medical student at the Perelman School of Medicine College at UPenn, Michael has accumulated experience in a variety of research projects and labs including working with PMC co-director, Dr. David Wolk and Dr. Ilya Nasrallah in the Penn Image Computing Lab, identifying new and better predictors of Alzheimer’s and dementia. He hopes to bring this research and the collaboration of other clinicians and researchers into developing areas where neurodegenerative diseases are not always well-understood and precision care is limited.

He envisions a new take on medicine, dubbed “precision neuroscience,” predicated on creating tests and treatments that can focus on the genetic and biological differences among certain populations.

These diagnostic tools would consider how one’s ethnicity may place them at a higher or lower risk of cardiovascular disease or the genetic components related to Alzheimer’s disease, Michael explained.

“I want to incorporate and work with many different populations and develop tools that take their individuality into account,” he said.

He hopes to bring this level of care to his family’s home of Vietnam, an avenue that’s starting to open up with the Perelman School of Medicine’s collaboration with Vietnamese conglomerate, Vingroup on a Center for Engagement in Southeast Asia.

Along with leadership from the Center for Global Health, Vingroup and UPenn will provide undergraduate and graduate medical training programs for students in VinUni and enhance graduate medical education and healthcare provisions in Vietnam’s largest, private nonprofit healthcare system, Vinmec. Both VinUni and Vinmec are Vingroup subsidiaries.

One was drawn almost 20 years ago, prior to the diagnosis and the other, in 2018. Michael sees the blue elephants still resemble each other two decades on.

“In helping Grandpa draw again, I see how unsung duties of caregivers transform everyone,” Michael writes, “caregivers have an opportunity to serve those in need and cultivate humanity.”