by Puja Upadhyay

Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics

Jason Karlawish, MD is Co-Director of the Penn Memory Center; Allison Hoffman, JD is a Professor of Law at Penn.

In the not-too-distant future, individuals may be able to learn their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease through biomarkers – measures of disease activity – detected up to 20 years before symptoms present. This information would allow individuals (and their loved ones) to prepare for future cognitive and functional decline, but it also has implications for the purchase of private long-term care insurance. In the Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics, Jalayne Arias, Jason Karlawish, and colleagues analyze whether, under current state laws, insurers could use biomarkers to deny coverage; in a companion commentary, Allison Hoffman places these findings in a larger context of a failing private market for long-term care insurance, and uses the study to make a case for social insurance for long-term care (LTC).

Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are among the most intensive users of long-term services and supports (LTSS) that help with “activities of daily living,” such as eating or bathing. These services are not considered “medical care” as defined in federal legislation regulating health plans; instead, they are regulated by the states. Medicare and private health insurance do not cover most LTSS, except in limited ways after hospitalization. LTSS are financed primarily by Medicaid (62 percent), individual out of pocket spending (22 percent), and private LTC insurance (12 percent).

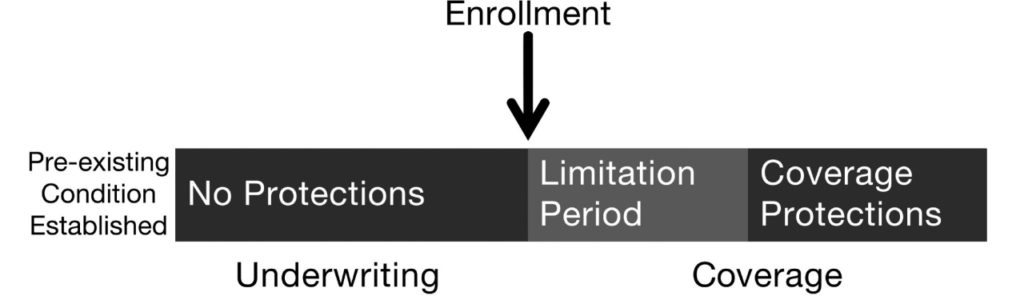

In their study, Karlawish and colleagues compared state laws to a model LTC act developed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). They found that state laws were largely consistent with the model act, which explicitly permits private insurers to use information on pre-existing conditions in their underwriting and approval process. As shown below, the model act also protects individuals from being denied coverage after a period of limitations, usually six months.

Source: DOI: 10.1177/1073110518782955 The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics – first published July 17, 2018

In a legal analysis, the authors find that biomarker status would likely be considered a pre-existing condition, subject to adverse underwriting decisions by insurers, including being denied coverage. Individuals who disclose their biomarker status and purchase a policy would have access to benefits after six months; however, many of those individuals may not be able to get as far as purchasing a policy. The findings suggest that individuals who learn their biomarker status may find it more difficult to purchase private LTC insurance, an important means for individuals to prepare for LTSS expenses.

In her commentary, Hoffman notes that these findings highlight critical flaws in the private market for LTC insurance. Underwriting practices protect insurers from adverse selection, where individuals at high risk are able to obtain coverage at underpriced rates. Simply banning insurers from considering biomarker status will not fix the adverse selection problem; people with Alzheimer’s biomarkers would be most likely to buy insurance, driving up prices that are already prohibitively expensive. If laws prevented insurers from considering biomarkers, they would look to other forms of medical information that are permissible to use to preserve their bottom line.

Hoffman argues that these realities and further advances in predictive testing reinforce the need for a mandatory, universal insurance program for long-term care.

One of many barriers to implementing such a program, Hoffman says, is failure to consider the full social impact of the problem. The majority of LTSS is delivered by unpaid, informal caregivers. Thus, the risk of long-term care is borne not only by the individual, but also by friends and family members who may become responsible for someone in need of LTC. “Next-friend” risk, as Hoffman calls it, can destroy a family’s financial security. By one estimate, the financial losses – including lost wages, pensions, benefits, and retirement savings – for the informal caregiver aged 50 or older who leaves the workforce early to care for an aging parent amount to over $300,000.

This problem isn’t going away anytime soon – in fact, it’s only getting worse. An estimated 5.5 million individuals live with Alzheimer’s disease in the US, a number expected to reach nearly 14 million in 2050. In general, the care needs of people with chronic illness are becoming more intensive, outpacing the ability of most families to pay for directly. The lack of protections for individuals who learn their Alzheimer’s disease biomarker status is only one example of the way the private market for LTC insurance is failing those who need it most, and adds to the case for pursuing policies more sensitive to the risks and financial insecurity individuals and families face.

This blog post is written by Puja Upadhyay, Policy Coordinator at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, and can be found in its original form here.