Dr. Jason Karlawish, co-director of the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, USA, spoke to Alzheimer Europe about his new book, which takes us inside laboratories, the homes of people living with dementia, carers’ support groups, progressive care communities, and Dr. Karlawish’s own practice at the Penn Memory Center.

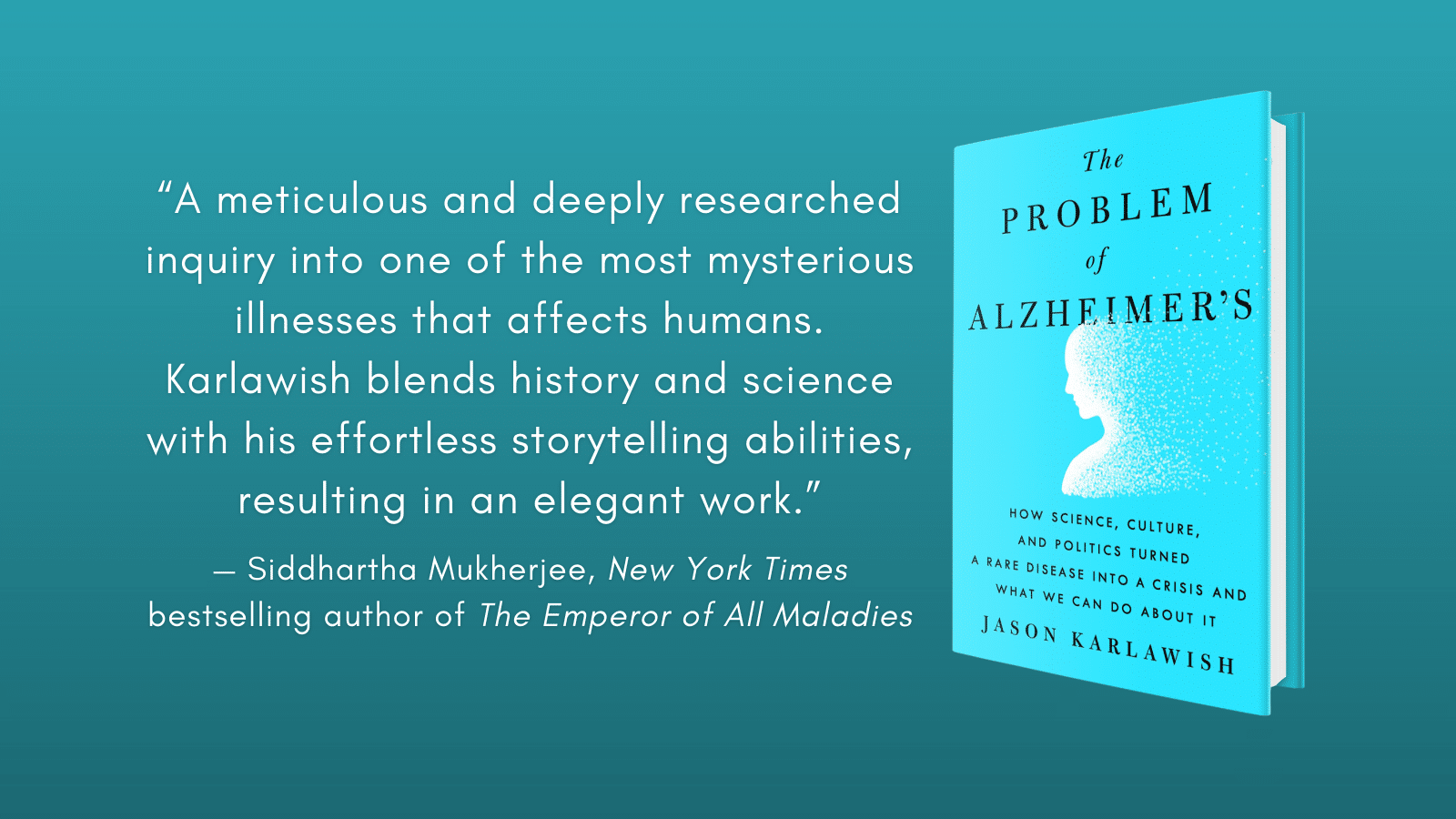

Why and when did you decide to write “The Problem of Alzheimer’s: How Science, Culture and Politics Turned a Rare Disease into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It”, and to take such a unique approach, combining your areas of expertise as a researcher, medical doctor, ethicist and storyteller?

For many, many years, more than ten, I’d been turning over the idea of “a book about Alzheimer’s.” About five years ago, I started writing in earnest. The stories of my patients got me going. I noticed something. My clinic notes were becoming more and more vivid, sort of sketches of stories. Each story was quite ordinary and deeply personal and unique, but I began to perceive something common: all were morally intense. They were stories about people struggling to live with a disease that early and relentlessly chips away at the very foundations of personhood: identity, privacy and ability to self-determine one’s life.

Alzheimer’s, I came to see, is a disease of a cherished but, in the arc of human history, a relatively young value. That is the value of autonomy. Not until the mid of the last century did most cultures come to accept that all adults ought to be allowed to determine their selves, to become a person. Matters of status such as wealth or birth order, or categories such as gender or race should not influence a person’s right to live as he or she chooses. Alzheimer’s takes this away. That’s what my patients and their caregivers were telling me. The doctor listened, the writer wrote and the ethicist analysed.

I also came to understand how I was practicing medicine in a revolutionary time. What my colleagues and I called Alzheimer’s disease and understood as a clinical disease was undergoing a revision. A person’s signs and symptoms – those stories of troubles with memory that cause problems with everyday life – they were no longer the foundation of the definition of the disease. Instead, the disease was being redefined by the seemingly objective measures of pathophysiology we call biomarkers.

I wanted to tell this story. I wanted to show how it would transform how we live with and make sense of disabling cognitive problems and living at the risk for developing those problems. The full narrative of the book came together when I realised the essential role of society in determining what this disease is and how we care for patients. The lives of patients and their caregivers are determined by the exercise of power and persuasion, or, in a word, politics. History shows how all too often, politics amplified their sufferings and losses. Simply put, the story of the 20th century is how science and culture turned what was once a rare disease into a very common disease, and then, quite quickly, politics made it a crisis.

You draw on the experiences of your patients and their families, sharing their struggles. Why was this important to you and were there any of their stories which particularly marked you?

I’m drawn to stories because they make sense of the myriad of sometimes contradictory facts. The stories that particularly marked me were those of persons who struggled to receive a coherent answer to a very simple question: “Doctor, what’s wrong with me?” In medicine, we say they are seeking a diagnosis. And then there were the stories of persons struggling to find care. They begin with challenges as fundamental as lacking even a language to talk about what they need and why they need it.

When I explain to a caregiver how a person living with dementia needs a day that is safe, social and engaged, and how a caregiver is the person whose job is to do this morally intense work, most have an eye opening moment. “That is me. That’s what I’m trying to do!”

Telling these stories in a sense gives them a voice. It shows those who are not caregivers or patients how real is this crisis.

As well as these personal testimonials of living with dementia, you also include a number of interviews with leaders in the field, particularly from the Alzheimer’s Association. What were some of the most important things you learned from them?

I learned how committed, passionate, even angry people had to settle down and make tough choices. They had to be willing to compromise and sometimes, in order to move forward, to pick the best of the worst options. That was the case when the founders of the organisation that would come to be called the Alzheimer’s Association disagreed over what to name their organisation.

Their disagreement reflected an enduring tension over the answer to two questions “Whom do we serve, the patients, their caregivers, both?” and “Is our focus all persons with dementia or only persons with one of the more common diseases that causes dementia, specifically Alzheimer’s?” In other words, is this organisation focused on the problem of dementia or the problem of Alzheimer’s? For much of the last quarter of the 20th century, the Association struggled to gain America’s attention. They faced notable obstacles.

One was the controversy over the size of this problem, over the count of how many people have Alzheimer’s disease. This number is critical to set the stage and command attention and resources. Obviously, the bigger the number, the more attention you command.

In 1990, the Association issued a public service announcement, delivered by Walter Cronkite, the nation’s most trusted reporter. He explained 4 million people had Alzheimer’s disease. This number was however in dispute. Many scientists argued the number was much lower. This disagreement spilled over into Washington, DC. Policymakers complained that if we can’t decide how big is the problem of Alzheimer’s disease, how are we supposed to know what to do.

Another obstacle was their struggle to convince Congress to support the expansion of Medicare to include long term care social insurance. The Association almost succeeded but ultimately they failed. The problem was that in 1980, at the same time they got started as an organisation, Ronald Reagan was elected president. The Reagan Revolution began. By the close of the century, expanding social insurance programmes was simply a political nonstarter in the Republican party. By the beginning of the 21st century, the Association had learned lots of lessons about American politics. I dug deep into the history that led up to the passage of America’s National Alzheimer’s Project Act. This story reads like a master game of chess.

The book looks to the history of Alzheimer’s disease, to help explain its present. Can you tell us a bit more about this progression and about how you hope things will develop in the future?

The history of Alzheimer’s can be summed up as the story of how science and culture turned a rare disease into a common one. Scientists saw the amyloid plaques, tau tangles and loss of neurons, and culture promoted the ethic of respect for autonomy. Together, they worked to transform the idea that an older adult with dementia was suffering from extreme aging, or senility, and so something medicine didn’t care about, into a disease called Alzheimer’s disease. Medicine now cared. But then politics turned the care of persons living with the disease into a crisis.

I came to see the seeds of this story in the early 20th century. The more I studied that time, the more I cast aside what I thought was the truth. I came to recognise how what happened at that very particular time and place amongst a small cadre of men (nearly all were men) was a story of science colliding with larger extra-scientific events, with politics.

Alois Alzheimer and his colleagues such as Max Bielschowsky, Oskar Fischer, Emil Kraepelin, and Franz Nissl were all German or of German culture. German was their language. The research and care they did unfolded in that milieu. And then it all fell apart as Germany fell apart. Beginning in 1914 with the Great War, and in its aftermath, painfully over some three decades, economic and social collapse led to the rise of vicious national socialism, anti-semitism, and anti-liberalism. World Word II was the awful conclusion.

The effect of all of this was to crush the German-based science Alzheimer and his colleagues were doing. They lost essential resources such as asylums where they could diagnose, treat and study patients, the funds for research, and, in the case of Fischer, their careers and lives.

In 1919, just two years after his promotion to Associate Professor at the German University in Prague, Oskar Fischer was denied tenure. The reason was not his academic skills but his religion. He was Jewish. His research ceased. In 1923, as he was campaigning for the German Democratic Liberal Party, anti-semites assaulted him. Sixteen year later, the Nazis occupied Prague, and Fischer’s lectureship was revoked. In 1941, he was imprisoned by the Gestapo at the notorious Theresienstadt prison. One year later, he was tortured to death.

One of the champions of the work of Alzheimer was Emil Kraepelin. In his 1919 essay, “Psychiatric observations on contemporary issues,” he wrote “a great misfortune has befallen us.” He assigned blame to people whose unchecked “primal dispositions” caused mass hysteria. He singled out the Jews.

When I read that, I nearly wept. This is how a field is ruined and also ruins itself. Now in the 21st century, history is not repeating itself (it never does) but it is recasting the early 20th century themes. Can we, who care deeply about persons living with dementia or who are caring for them, muster our nation’s collective will to come together and support science and the social policies needed to care for the millions of persons living with dementia? We do this in the face of challenges such as refugees from collapsing nations, climate change, a decline in family size and so a dearth of “informal caregivers,” and a global pandemic. Some liberal democracies have embraced harsh nationalism and politicians who promote policies that undermine our confidence in science and its ability to help us solve our problems.

You also explore national policies (and the lack of them) in the US throughout the last century, and how they impacted progress in research and care. From your perspective, what are the most important areas for policymakers (in the US and overseas) to focus on, to improve the situation for people with dementia and their families?

We have made spectacular progress in understanding how the pathologies that cause dementia unfold in a person’s brain and we’re making impressive progress discovering therapies that target some of those pathologies. Someday, perhaps soon, clinicians will have treatments that can slow the pace of some of these diseases. But policymakers need to attend to a simple fact. We’re not going to drug our way out of the problem of Alzheimer’s (as well as Lewy Body Disease, Frontotemporal Lobar Disease, TDP-43, vascular disease, and so on). These diseases are like cancer or heart disease. They are complex.

So what should they do? Policymakers need to focus on how their nation can deliver fair and equitable care to persons living with disabling cognitive impairments and their caregivers. This means providing access to quality long term care services and supports. This needs to serve two groups: persons who are at risk for disability who must plan for care and also for persons who are living along the continuum of disability. It is simply unacceptable that families are left to figure these things out on their own, and, once they do, pay and pay and pay until there is nothing left and so welfare steps in, or the person has died. It is simply unacceptable that stigmas crush their well-being and subject them to discrimination in the work- place and community.

This interview was originally published in Dementia in Europe Magazine.