By Danny Yarnall

Penn Program on Precision Medicine for the Brain (P3MB) researchers and their collaborators are calling for a revision of studies to better consider persons living with dementia in order to provide vital data for future care interventions.

Embedded Pragmatic Clinical Trials (ePCTs) try to make research look as much like actual care as possible. They are scored on their “pragmatism” or how closely they resemble standard care. If a study is designed well and its methods closely hew to what clinical care looks like in a particular care setting, it can provide highly actionable information that healthcare professionals and policymakers can use to improve care for people in that care setting.

Currently, relatively few ePCTs are being used in Alzheimer’s research. Meanwhile, a fragmented healthcare system, compounded by a lack of specialists to treat the growing number of persons with dementia, often falls short of providing high-quality care to the some five million people living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States and supporting their care partners. While potentially valuable, ePCTs in persons living with dementia present some ethical hurdles that need to be considered and addressed.

Dr. Emily Largent is the lead author for the paper published in the Journal for the American Geriatrics Society.

Clark Scholar Emily A. Largent, JD, PhD, RN; Spencer Phillips Hey, PhD; P3MB Research Program Manager Kristin Harkins, MPH; Allison K. Hoffman, JD Steven Joffe MD, MPH; Julie C. Lima, PhD, MPH; Alex John London, PhD; and P3MB Director and Penn Memory Center Co-Director Jason Karlawish MD, part of the National Institute on Aging-funded IMPACT Collaboratory, published a paper in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society outlining issues with ePCTs and proposed solutions for how to conduct them with persons living with dementia in mind.

The paper is part of a special edition of the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society on ePCTs. The assembled papers showcase the many ways in which the members of the IMPACT Collaboratory are seeking to increase the nation’s capacity to conduct ePCTs and improve the care of people with dementia — other papers address issues like health equity and stakeholder engagement. The entire issue is available here.

The authors’ main ethical concerns with ePCTs as they pertain to the safety and privacy of persons living with dementia mainly surround identifying who is a subject in the study and how to inform them. The way many ePCTs are often designed interventions are done at the “unit” level, like an entire adult day program or nursing home. Randomized assignment of subjects to the intervention or control groups are also done at this level.

The authors laid out a scenario in a nursing home. The nursing home staff receives new training as part of the intervention arm. Researchers will want to see effects the training has on how the staff performs their duties and how residents receive the effects of that training. It can be difficult to identify exactly who is being treated and therefore what protections need to be offered with so many interactions among participants. In addition, the notification or informed consent process that is common in academic research is often “in tension” with ePCTs’ study design.

“Informed consent is usually thought to be an essential element of ethical research. But, when you are conducting pragmatic trials, it’s sometimes desirable to waive consent altogether so as to get as close to approximating real-life conditions as possible,” Dr. Largent said.

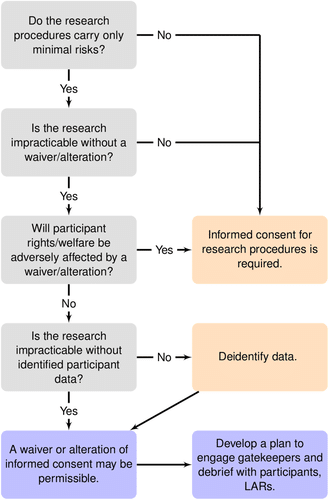

An example of a flow chart that could be used to determine who would receive informed consent to a waiver in an ePCT.

When there are compelling scientific reasons for waiving consent, the next step is to determine whether waiving consent is consistent with research ethics and with the regulations protecting research subjects. The authors walk through using established criteria for when and how to obtain a waiver for informed consent, such as if obtaining that consent would interfere with the trial or if waiving consent would endanger an individual’s rights and safety while highlighting particular considerations for persons living with dementia.

There’s also the challenge of managing conflicts of interest, such as researchers who may have a financial interest in the program they are testing. Opportunities to stem this risk could be simply disclosing the funding or, in some cases, by asking the conflicted individual to step away in favor of someone else.

The authors also recommend training and guidance on study regulations for staff in a setting like a nursing home who may not be accustomed or aware of the rules for ethics in research.

It is the authors’ hope that developing solutions for pragmatic trials that protect persons living with dementia without hindering research can benefit dementia care on the whole.

“There is a lack of evidence-based interventions for people living with dementia and their care partners. A goal of conducting pragmatic trials is to improve the evidence base and — as a result — improve care for this population,” said Dr. Largent.