By Meghan McCarthy

Editor’s note: This article is part of an ongoing coverage of the 2024 Alzheimer’s Association’s International Conference (AAIC). To view all highlights, please click here.

Each morning, Sarah wakes up early, makes a pot of coffee, and turns on the news. The ritual had been a part of her routine for decades. In their retirement years, Sarah’s partner, Jodi, slept in a little later but always joined Sarah eventually. Together, the two sip their coffee and watch the stories of triumph and tragedy alike on their morning station.

Sarah doesn’t remember exactly when a change in Jodi started. Watching together, the pair used to get quite moved by the morning highlights. Now, Jodi remains mostly unaffected. It’s a subtle change, but one that Sarah noted after becoming particularly emotional one morning. Not only was Jodi very uninterested in the story, but also unconcerned about her partner’s emotion.

As time passed, Jodi’s withdrawn personality became more noticeable. In social settings, Jodi began acting without regard for social norms. She lacked an interest in others’ emotions. Jodi was not aware of these changes. As a loving partner, Sarah began to worry. Together for decades, it was clear to her that Jodi’s empathetic and caring nature was being replaced with a different personality.

After seeing several clinicians, Jodi was eventually diagnosed with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD).

Empathy loss is a hallmark symptom of this form of dementia.

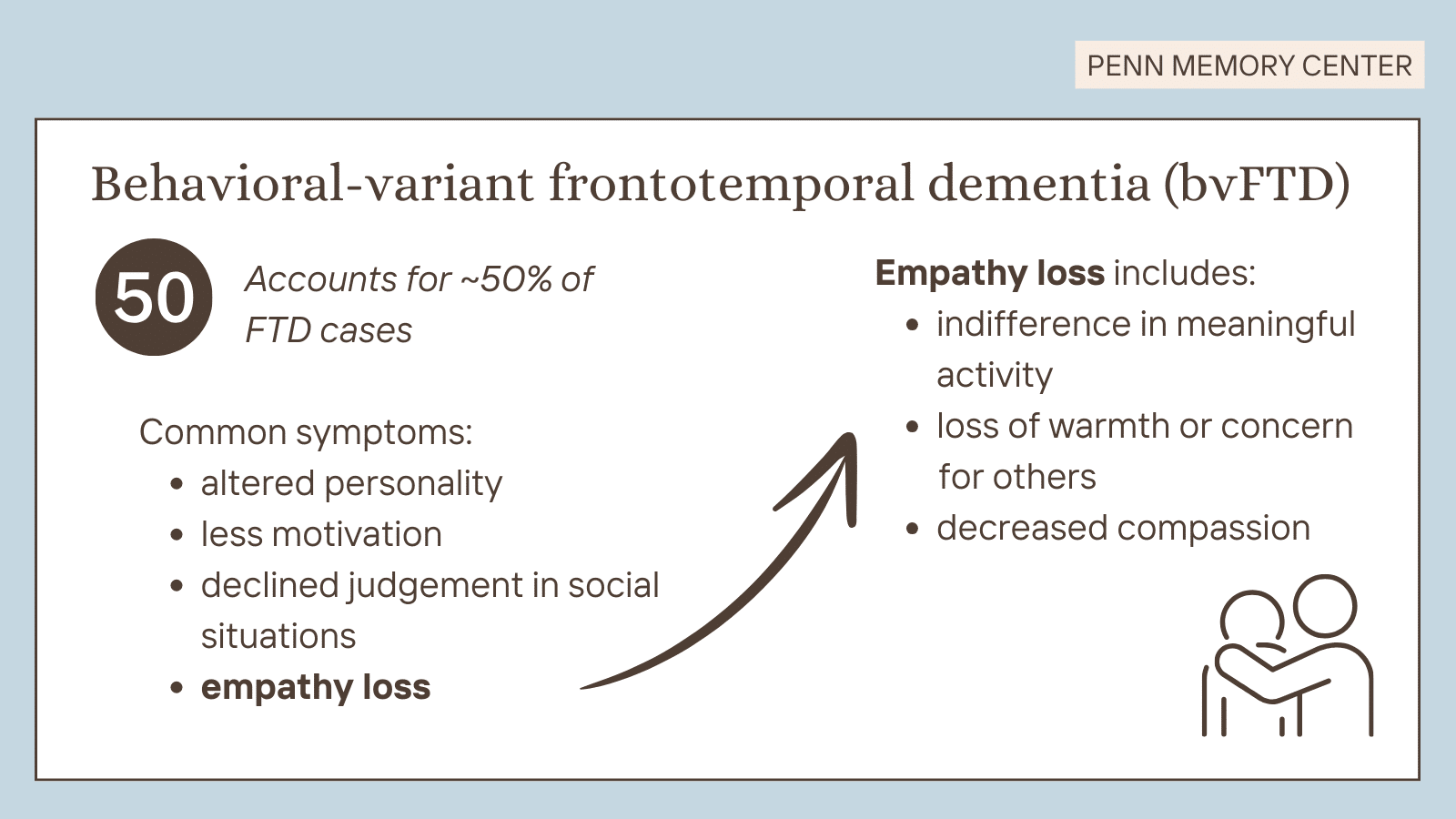

BvFTD is a common form of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and comprises almost half of FTD cases. Common symptoms in bvFTD patients include altered personality, less motivation, and declined judgement in social situations.

Empathy loss, specifically, can be one of the first symptoms of bvFTD that family members notice. Individuals may show indifference to meaningful activities, loss of warmth or concern for others, and less compassion. Often, patients with bvFTD are not aware of these changes.

For patients like Jodi, empathy loss can begin as a subtle change and increase over time.

The symptom comprises two main shifts: cognitive and emotional. The former refers to recognizing when others are upset and putting oneself in another’s shoes, while the latter means expressing an appropriate emotional response in given situations.

At this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), Penn Memory Center (PMC) Clark Scholar and Penn Frontotemporal Degeneration Center Clinical Neuropsychologist Emma Rhodes, PhD, MA, is presenting findings on the relationship between empathy loss and heart rate variability (HRV) in bvFTD patients.

HRV is a term that encompasses fluctuations in the time between heartbeats throughout the day. This occurs naturally. For example, heart rate rises with physical activity or in stressful situations. Heart rate can lower when sedentary or relaxed. Higher HRV reflects greater fluctuations throughout a given period of time.

Dr. Rhodes, who has a background in studying empathy loss, was interested in whether a loss in empathy would affect HRV.

“I’m really interested in physiologic mechanisms of behavioral symptoms,” Dr. Rhodes said. “Essentially what’s happening in the body and how that changes over the course of an illness like FTD, where we see a progressive loss of neurons that control some of our internal feelings and states. How does this lead downstream to certain behavioral symptoms?”

To accomplish this, Dr. Rhodes looked at data from the ALLFTD study, a large observational study that aims to help FTD drug trials by providing important clinical information about the disease. Organized as a consortium, the project has numerous study sites, and Penn is one of them. The study recruits both persons with a diagnosis of FTD, as well as individuals who may be at risk of developing FTD based on their family history or a genetic variant in the family.

ALLFTD participants have vital signs collected at each research visit. Amongst measures of blood pressure, height, and weight, a two-minute resting heart rate assessment is also done.

Dr. Rhodes analyzed years of heart rate data from ALLFTD participants to see, as symptoms potentially progressed, if HRV was affected. She compared heart rate measurements across different study visits. For some, this amounted to comparing over 10 years of clinic visit data.

She also utilized information about empathy loss within participants, assessed by study partners completing questionnaires. For example, Sarah could complete questionnaires on her observations about Jodi to aid clinicians’ understanding of symptoms Jodi was not otherwise aware of.

Dr. Rhodes found opposing results between bvFTD and healthy participants.

Specifically, she found that individuals with FTD mutations, especially those who were pre-symptomatic, showed a tendency for their resting heart rate to increase over time. This increase was associated with a decline in emotional empathy. Unaffected family members without the mutations, on the other hand, had less change in resting heart rate over time, with no major change in emotional empathy over time.

“People with FTD mutations who had an increase in heart rate were showing greater empathy loss while they were enrolled in the study,” Dr. Rhodes said.

While the exact reasons for these findings need further research, Dr. Rhodes believes the differences are tied to the way FTD affects specific structures within the brain.

Some of the first areas impacted by FTD include the medial frontal lobes and the anterior insula. The anterior insula is responsible for integrating environmental cues into internal bodily signals. This area is vulnerable to cell death due to FTD. As a result, the body’s physiologic response to the environment may be affected, which would explain the increase in resting heart rate and loss of empathy observed in bvFTD patients.

A promising start, Dr. Rhodes has plans to further research this relationship.

Notably, she is interested in studying whether there is a stronger increase in heart rate when an individual with a genetic mutation for FTD converts from being asymptomatic to symptomatic.

“We are interested in the idea that HRV could be a biological marker of disease manifestation in genetic mutation carriers,” Dr. Rhodes said. “This could be a very helpful measure because it is more objective than asking family members how loved ones are doing. It could provide physiological measures to improve diagnosis and early detection.”

She is also interested in collecting longer heart rate measurements and comparing them to these findings.

For families such as Sarah and Jodi, Dr. Rhodes research is an important step in furthering diagnostic and care measures for bvFTD patients.

“It’s very challenging to see your loved one change in this way,” Dr. Rhodes said. “Especially as a caregiver, where you are putting hours of work every week to try to care for someone who may not care back.”

To learn more about Dr. Rhodes, please click here.

To read more about Dr. Rhodes’ background at as a PMC Clark Scholar, please click here.

To read about Dr. Rhodes work with empathy loss and smartwatches, please click here.