By Meghan McCarthy

Editor’s Note: This article is part of the Disability and Dementia Series, which is an ongoing project aimed to highlight Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) experiences in individuals with intellectual disabilities.

In a 2017 testimony to congress, advocate Frank Stephens stated: “I cannot tell you how much it means to me that my extra chromosome might lead to the answer to Alzheimer’s.”

[Above: Video of Frank Stephens’ testimony]

A powerful moment, Stephens’ message was clear. Individuals with Down syndrome (DS) must and should be included in Alzheimer’s disease research.

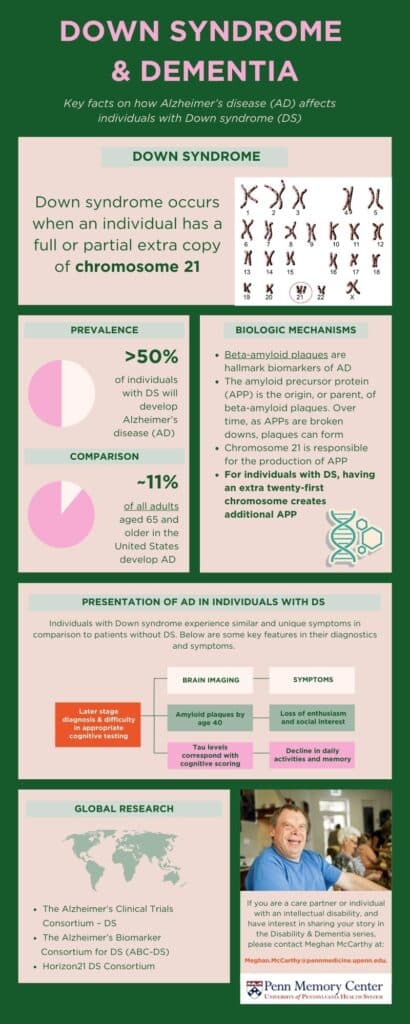

It is estimated that over 50% of individuals with DS will develop Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as they age. To put it in perspective, approximately 11% of all adults aged 65 and older in the United States develop AD.

Despite this, many disparities exist in standardized care and research inclusion methods for individuals with DS.

Biologic causes for increased risk

Individuals born with DS have an extra copy of chromosome 21, which is a genetic structure comprised of an individual’s DNA.

Beta-amyloid plaques are hallmark biomarkers of ADRD. These plaques cause damage, or neurodegeneration, within the brain, resulting in cognitive decline. The amyloid precursor protein (APP) is the origin, or parent, of beta-amyloid plaques. Over time, as APPs are broken downs, plaques can form. Chromosome 21 is responsible for the production of APP.

For individuals with DS, having an extra twenty-first chromosome results in additional production of APP. Ultimately, this causes DS-Associated Alzheimer’s Disease (DASD). Autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD), on the other hand, is inherited and caused by gene mutations amongst individuals without DS.

While researchers don’t fully understand this mechanism, many believe additional risk factors associated with chromosome 21 are connected to this heightened risk.

For example, research suggests that insulin resistance, heightened inflammation, and increased production of other molecules may also be key factors in why those with DS develop AD at higher rates.

Symptoms for those with DS

AD progresses along a spectrum of symptoms, from early-stage to late-stage, with varying intensity and timing. In individuals without DS, research suggests brain changes may occur 15-20 years before symptoms begin.

For those with DS, AD occurs earlier in life. For example, brain imaging has shown that nearly all individuals with DS over the age of 40 have beta-amyloid plaques. This buildup begins in late teenage years in memory-related brain regions.

Current research suggests that the risk of developing AD for individuals with DS is approximately 23% at age 50, 45% at age 55, and 88% or more at age 65.

As DS is an intellectual disability, it can be harder to notice AD symptoms in patients with DS. Often, friends, family, and care partners are the first to notice change.

For individuals with DS, common AD symptoms include lower interest in social experiences, expressive discussion, and enthusiasm within their routine. Like adults without DS, individuals with DS also experience a loss in episodic memory, which is responsible for functions and activities of daily living.

Diagnostics

Adults with DS should access diagnostic memory care if they are demonstrating signs of AD.

Many assessments that measure cognitive decline are evaluated based on standards for individuals without DS. This poses a challenge when diagnosing individuals with DS, as there is no single, standard cognitive assessment used for early-stage dementia in patients with DS.

To address this, clinicians recommend evaluating baseline intellectual, behavioral, and social function by the age of 35 in individuals with DS. This will allow direct comparison if future testing is needed due to cognitive decline.

Brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential in evaluating brain atrophy, or loss, in all patients with AD.

In adults without DS, measuring beta-amyloid buildup over time is often done. However, because individuals with DS have an accelerated buildup of this protein, amyloid focused imaging can be less effective for diagnostics.

Current research suggests that cognitive assessment scores align with tau levels, another AD biomarker, in DS patients. For example, individuals with lower tau levels exhibit higher cognitive scoring. Thus, many support the use of tau PET scans for DS patients in measuring AD-cognitive decline accurately and in real time.

blood-based measurements of beta-amyloid are also being explored with findings indicating higher levels in individuals with DS compared to those without.

Future Research

Individuals with DS are often excluded from AD clinical trials due to barriers in research design and cognitive assessment methods. As individuals with DS have diverse intellectual abilities, more comprehensive and tailored methods for evaluating cognition are needed in the ADRD field.

Research focused on their disease experience is essential to furthering equitable diagnostic methods, care, and drug availability for those with DS.

Current advocacy and research efforts include:

- The Alzheimer’s Clinical Trials Consortium – DS: Aims to accelerate the development of effective interventions for Alzheimer’s disease in DS through two clinical trials with participants across the globe.

- The Alzheimer’s Biomarker Consortium for DS (ABC-DS): The largest clinical trial studying biomarkers of AD in individuals with DS, this longitudinal study seeks to identify sensitive neuropsychological measurements of cognitive decline, biomarkers, and neuropathologic features associated with AD impairment.

- Horizon21 DS Consortium: Based in Europe, this consortium aims to prevent or delay AD in individuals with DS through investment in clinical trials across 11 locations.

In future articles with the Disability & Dementia Series, PMC will explore innovative research and the lived experiences involving individuals with DS.

For further information about DS and AD (lay audience), please click here.

For an in-depth manuscript highlight (research audience), please click here.

To read more about Frank Stephen’s testimony, please click here.

If you are a care partner or individual with an intellectual disability and have interest in sharing your story in the Disability & Dementia series, please contact Meghan McCarthy at Meghan.McCarthy@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.