By Michele W. Berger, Penn Today

Mid-morning on a Wednesday in early May, Jean Haskell tries to quiet a dozen chatty adults on a Zoom call. “Alright, everybody, we’re going to start. We’re going to do a lot today. We’ll be getting ready for a performance next week, and we’ll be telling some jokes.”

She asks participants to say their name along with an adjective and gesture for everyone else to copy.

“My name is Charles. An adjective? Crude,” says one person, before holding up his thumb in hitchhiker fashion. There’s a collective chuckle.

Hellacious Helen makes horns on her head with two fingers and Suspicious Susan pretends to hold a telescope up to her eyes. After each one, the participants mimic the speaker, laughing at the silliness of it all. But as Haskell—who introduces herself as Jazzy Jean, replete with jazz hands—hoped it would, the exercise breaks the ice perfectly.

It’s crucial that the participants of this improv workshop, who have named themselves the Funny Philadelphians, feel comfortable because they either have memory impairments themselves or care for someone who does. The group was intended to be in person. Then in March, the pandemic made it increasingly clear that was no longer safe or feasible, so the Penn Memory Center moved the Cognitive Comedy program online. Since then, two eight-week remote sessions have run, the second of which finished at the end of July. A fall session will start mid-September, still virtual.

“The objective is to promote social engagement, to use your brain in a creative way,” says Megan Kalafsky, program coordinator of Time Out, a joint initiative from Penn and Temple University that runs Cognitive Comedy. “We spend most of the time playing improv games, to get people thinking, but we also make sure it’s accessible to everyone.”

Going remote

Face to face, it’s challenging to make an activity’s appeal universal for a large group, but adding the remote layer required even more creativity. Haskell was up for the task.

She’s been doing improv since 1997, a hobby she began as an antidote to her day job as an organizational psychologist. For the past decade, she’s taught improv to older adults at Temple. One of her students, also a patient at the Penn Memory Center, told Haskell about the Cognitive Comedy group. “She asked me if I’d be interested in teaching it,” Haskell says. “I was intrigued.”

In January, Haskell and Kalafsky met to create a plan for restarting the program, which had been on a several-year hiatus after the previous instructor left. They organized a series of Memory Cafés set for March, and hoped to hold the improv group in person at Penn. “Then everything changed, of course,” Kalafsky says. COVID-19, particularly harmful to the vulnerable population who would take part in Cognitive Comedy, was spreading rapidly around the country and campus was shutting down.

“The improv group that I’ve been in for 20 years was meeting virtually,” Haskell says. “I mentioned this to Megan. I said I’d be interested in doing a pilot program online. They loved the idea, and we got started right away.”

Community-building

After the Zoom call introductions, Haskell wants to know what kind of week everyone has had—terrible, good, boring—then asks participants to tell their jokes, at least a couple of which turn out to be coronavirus-themed.

“There’s a new restaurant in town called Karma. They don’t hand out menus because of the virus. Customers just get what they deserve.” Big laughter.

“Since we’re all still in quarantine, when we do our improv performance next week, how will we know if it goes well? If it goes viral.” More laughter and smiles.

Next, 74-year-old John Morris takes a turn. He tells one about an Englishman, a Scotsman, and an Irishman who walk into a bar. It’s a hit. “I write very few jokes. I usually steal them,” he admits later. “That joke’s an oldy.”

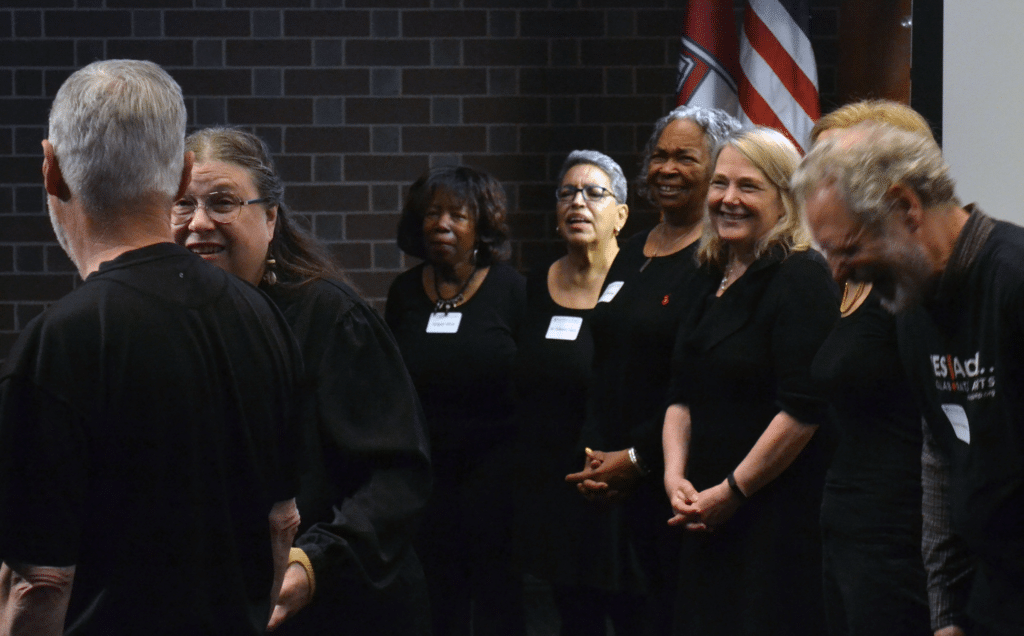

Before the pandemic, Cognitive Comedy participants met in person on Penn’s campus. The second of two eight-week remote sessions finished at the end of July. The fall session will start in September.

Morris himself isn’t cognitively impaired, but both of his parents had Alzheimer’s, and when he wanted to get tested for it he was told the risk of false positives was too high. Instead, his physician suggested he might volunteer to participate in research happening in the field. Through those conversations, he learned about Cognitive Comedy, which he’s been a part of for about five years. “After my first class, I thought, ‘This is fun. A bunch of old people getting together and having fun,’” he says.

Of course, Haskell wants everyone to enjoy the sessions; that’s why she has participants tell jokes and play goofy games. But there’s much more to it. The class aims to up the confidence of participants—most of whom are in varying stages of cognitive decline—as well as to provide a place for them to socialize and engage with a group and to challenge themselves. “Meg and I want them to feel as if they can accomplish something, to feel connected to other people and to build a community,” says Haskell.

Ask Morris whether that’s happened, and he offers an unwavering yes. “We have people from all different backgrounds, economic levels, ethnic groups,” he says. “We have one thing in common: We like to get together and do corny improv. Friendships grew out of that.”

Isolation antidote

Kalafsky offers another function for the program, one whose importance increased in parallel with quarantine orders: It’s a way to combat social isolation. Research from February 2020 showed that for seniors, feeling isolated and lonely can significantly increase their risk for dementia and other serious medical conditions. And that work didn’t account for COVID-19.

“Social isolation is something that we’re all feeling right now but is something that’s not new or surprising to this demographic,” Kalafsky says. “This group is a nice way to see other people in a similar stage of life and to make new friends.” Beyond that, it can offer respite for caregivers.

In non-pandemic times, Time Out pairs college students with older adults to provide them companionship and give caregivers a break. For the past several months that hasn’t been possible. “We were looking for different creative outlets,” says Kalafsky. “We have caregivers who get their loved ones set up and then take time to sit by themselves, take a nap, take care of things around the house. We also have caregivers who participate.”

That latter cohort, she says, does this because Cognitive Comedy is just plain fun. Participants throw imaginary balls of various sizes to one another across the Zoom boxes. They tell fictional stories about a random object Haskell pulls from her bag. They show off original and “stolen” jokes and give performances. Yet as Morris puts it, there’s no pressure to excel.

“When somebody makes a mistake,” he says, “we don’t do anything but cheer them on.”

The Cognitive Comedy sessions are well-attended and well-loved. People return for seconds. None of the participants will likely soon forget what they come away with. And, given the intended audience, that’s precisely the point.