The first of three tips from AARP’s Global Council on Brain Health. Find tips 2 and 3 below and the complete infographic here.

By Meghan McCarthy

Each night, before bed, William* takes out his book of sudoku puzzles. Patiently, he pencils in numbers 1 through 9 across the puzzle — always in pencil, as he inevitably ends up needing to erase some guesses.

Some nights he completes the whole puzzle, other nights he finishes just one section, but when he feels he’s hit enough of a milestone, he turns out his light, takes off his glasses, and goes to sleep.

The routine was suggested by William’s wife, who heard that brain games like sudoku help with cognitive functioning. When William began displaying symptoms of dementia, she bought a collection of puzzle books and left them on his bedside table. And so, sudoku became their nightly ritual.

Sudoku is one example of brain games, which are tasks that are advertised as ways to exercise your brain and sharpen cognition.

Brain training is a subset of brain games.

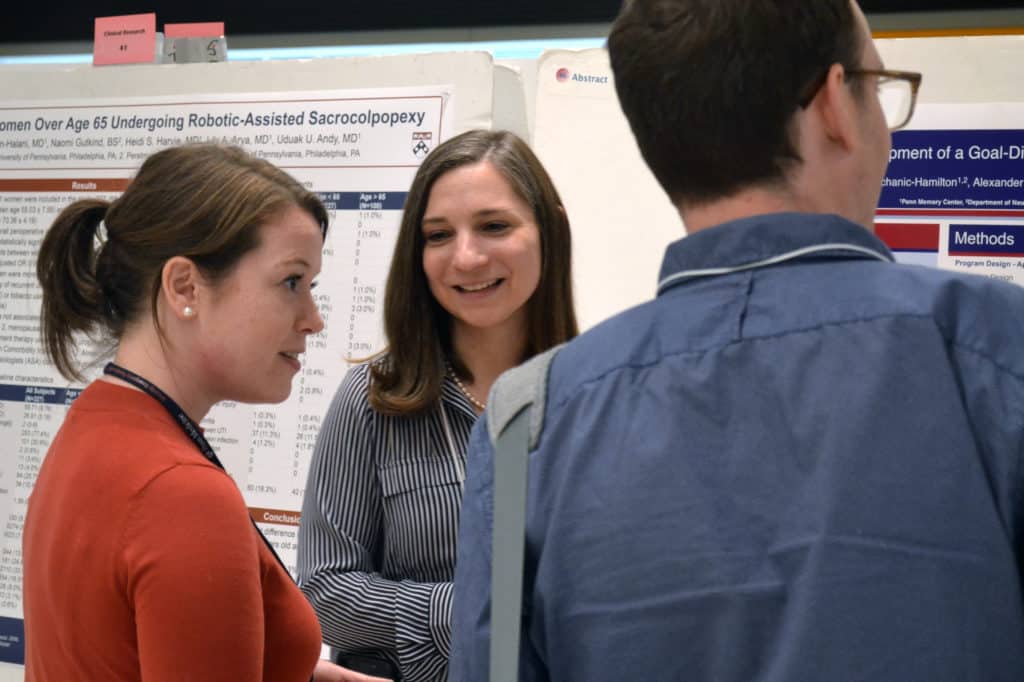

“Brain training is typically some kind of computerized task that is done on a schedule to try to strengthen a particular area of thinking,” said Dawn Mechanic-Hamilton, PhD, ABPP/CN, director of the Cognitive Fitness Programs and Neuropsychological Services at the Penn Memory Center.

Dr. Dawn Mechanic-Hamilton (center)

Certain websites and apps market brain training products as a resource to slow or prevent cognitive decline. But there isn’t thorough evidence to support that these products improve cognitive functioning in older adults. Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton argues that the best way to keep your brain active comes from engaging experiences.

“Learning and challenging your brain throughout your life has a protective effect over the course of your life” said Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton. “I tell people to pick tasks and hobbies which will be challenging and enjoyable to stick with.”

When picking an activity to challenge your brain, it is important to pick something that continues to get harder.

Unlike computerized products, which can be isolating, best types of activities for the brain are what Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton calls a “two for one,” because they involve both socialization and learning. This includes taking an exercise class with friends, attending book clubs, or going to lectures on a favorite topic.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to brain engaging activities, however.

An older adult with unimpaired cognition will require different challenges than an individual living with dementia. Brain-engaging activities will also change throughout one’s life.

For the recently retired, Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton suggests taking up hobbies or interests that were once a part of earlier life or something they’d always wanted to try.

To try to help a loved one stay cognitively active, Dr. Mechanic-Hamilton suggests activities of nostalgia, such as looking through and discussing photo albums, playing a loved one’s favorite music, or cooking family recipes.

*Pseudonym