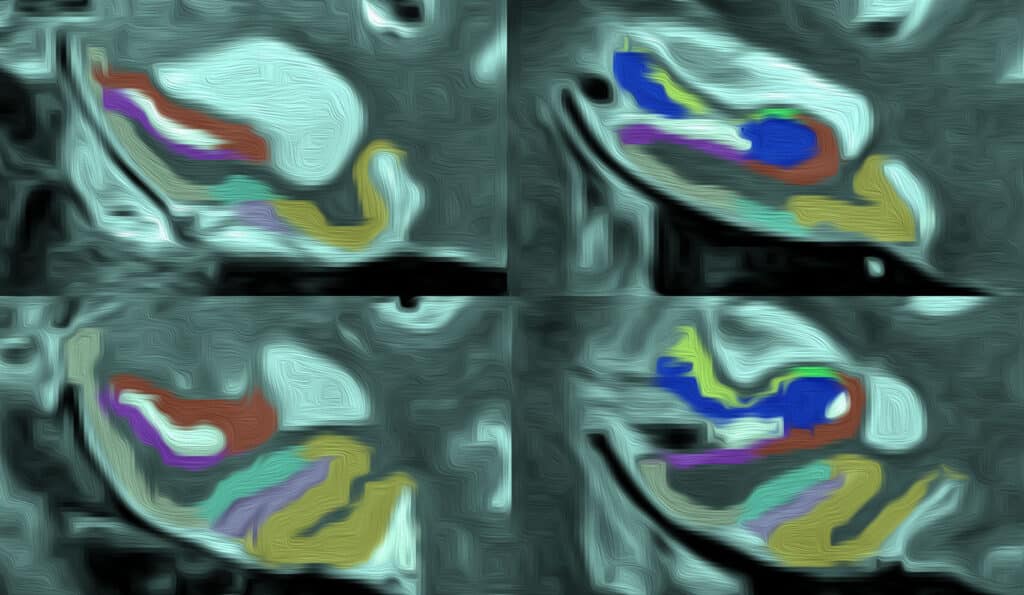

Graphic illustration of a T2-weighted MRI with MTL subregion segmentation.

By Varshini Chellapilla

Specialized high-field MRI scanners are some of the most advanced machines in medical research currently and have been equipped to study epilepsy, neurological disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease across many research fields. At Penn, the ultra-high-definition resolution of these MRIs helped researchers study the patterns of atrophy, or loss in volume due to degeneration of cells, in patients with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA).

“Volume loss in this region of the brain has been investigated in the past but never with scans as good as these,” said Laura Wisse, PhD, the principal investigator for the study. “With higher resolutions, we were able to measure this particular region of the brain in a much more detailed way.”

Dr. Wisse’s study was titled “Cross-sectional and longitudinal medial temporal lobe subregional atrophy patterns in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia” and published in the Neurobiology of Aging.

Dr. Wisse is currently an assistant professor at Lund University in Lund, Sweden. Beginning in 2014, she was a postdoctoral trainee at Penn Memory Center in what would later be called the Christopher M. Clark Scholars Program. Under the guidance of David Wolk and Paul Yushkevich, Dr. Wisse continued her work focused on using ultra-high resolution to study specific patterns of atrophy in the medial temporal lobe of the brain for five years at PMC.

Dr. Laura Wisse is flanked by Alzheimer’s Association Delaware Valley Chapter Executive Director Kristina Fransel and Dr. Rebecca Edelmayer, Alzheimer’s Association Director of Scientific Engagement, after receiving a research grant award in 2019.

“The medial temporal lobe is an interesting region of the brain to study from different perspectives,” Dr. Wisse said. “It is so important for memory and spatial navigation but keeps coming up whenever you think about different causes of dementia, other pathologies, or even psychological diseases like depression and epilepsy.”

The medial temporal lobe consists of different structures of the brain that are collectively responsible for memory. Dr. Wisse and her team studied the perirhinal cortex — a particular structure in the medial temporal lobe that is responsible for semantics — in patients with svPPA, a variant of frontotemporal dementia that causes problems in conceptual knowledge, understanding the meaning of words, and naming objects. The researchers studied the way that this particular part of the brain showed atrophy as a result of svPPA.

“With all these types of dementia, we often do not know what the real causes of the volume loss in the brain or the memory problems or any other cognitive problems that these patients have,” Dr. Wisse said. “Part of why we were interested in doing this is to see if there is a specific pattern of atrophy in the medial temporal lobe that is very specific for this pathology, or at least when this pathology occurs in the medial temporal lobe.”

The high-resolution scans revealed that svPPA showed significant loss in all left and several right areas of the medial temporal lobe. The data collected in the study also allowed Dr. Wisse and her team to study the change in the brains of participants over time.

“Typically, researchers compare patients with dementia to participants without dementia in a control group. And then, based on the difference in volume of loss of the brain region, we say, ‘Oh the patient lost volume, so there is a change.’ But that is only a measurement at one point in time,” Dr. Wisse said. Penn researchers observed changes over time, which ensured more accurate measurements that are useful to understanding the progression of the disease and for future clinical trials.

Additionally, the study stresses that the study of atrophy patterns in the medial temporal lobe can provide insight into the characterization of the atrophy and provide better biomarkers to study the progression of the disease.

Dr. Wisse has two follow-up studies that aim to create better measurements for the medial temporal lobe subregions and to make better automated methods for patients with svPPA. Her work at PMC also informs her future studies comparing atrophy patterns in patients with early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.