By Chloe Elmer

Sometimes, in traveling, the fastest route to a destination requires the traveler to abandon familiar side roads in favor of a newly constructed highway.

In Alzheimer’s disease research, that highway is biomarker-based research. In a special report for the Alzheimer’s Association, Penn Memory Center Co-Director Dr. Jason Karlawish wrote that biomarkers are changing the future of Alzheimer’s disease research.

“In the history of medicine,” Karlawish wrote, “one means to progress is when we make the decision that our assumptions and definitions of disease are no longer consistent with the scientific evidence.”

As biomarker-based research advances, Alzheimer’s disease could become readily identifiable early on and treated before any significant impairment in a patient is evident. This would be different than a drug approach to treating the disease after it becomes symptomatic, which is where past and current studies have repeatedly yielded negative results.

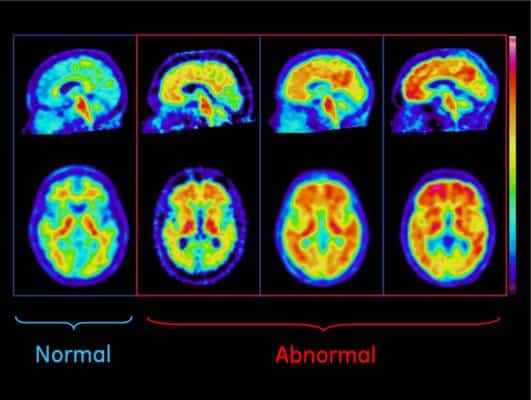

Clinicians use biomarkers when diagnosing or ruling out diseases or assessing an individual’s risk of developing a disease. Researchers are currently assessing Alzheimer’s biomarkers such as the accumulation of the proteins beta-amyloid and tau in the brain, which can be measured using brain imaging or the levels in cerebrospinal fluid, as well as changes in brain volume and activity.

Karlawish calls the development and validation of these biomarkers through research for Alzheimer’s disease “a top priority.”

With more than five million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s disease and 480,000 older adults estimated to be diagnosed this year, further research in validating these biomarkers could play a great role in the future of the disease. Identifying and validating biomarkers can also help enroll the right people in clinical trials, monitor the effectiveness of treatments, and eventually, provide early intervention with those more at risk to the disease. Karlawish wrote that future data from clinical trials using Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers will shape the way researchers, clinicians, and patients understand the disease.

“Biomarker-based clinical criteria and future clinical trial data will continue to change our understanding of who has Alzheimer’s disease,” Karlawish wrote, “as improved diagnostic techniques will provide earlier identification of cognitive impairment, and of the brain changes that lead to it.”

With continued research and the development of ethical guidelines, the hope for the future of Alzheimer’s disease is that it can one day be treated with early intervention as a chronic condition, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, and no longer as an “irrevocable cognitive and functional decline and death.”