Florence Collins-Hardy (left) with her husband, Robert. Collins-Hardy has been an ABC study participant since 2014. (Linnea Langkammer / Penn Memory Center)

by Linnea Langkammer and Joyce Lee

Sandra Shulan is sitting next to her partner, Harry, in the Penn Memory Center (PMC) waiting room at the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine. She isn’t nervous. In fact, she’s quite looking forward to it.

Her first ABC study visit.

Marianne Watson, then the study clinician, greets Shulan and leads her through the glossy white hallways. Together, they enter an exam room with high ceilings and a wall of windows overlooking a railway. The windows fill the room with natural light.

The ABC (Aging Brain Cohort) study is the largest and longest of the studies conducted at PMC. A longitudinal observational study, ABC sets out to better understand Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy brain aging.

Data from the ABC study is shared with researchers across the nation via the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, established by the National Institute on Aging in 1999.

Shulan’s first ABC visit begins with the daunting pile of consent forms. There’s a lot for her to go over today: detailing the annual visit, scheduling brain scans, and perhaps most importantly, managing her expectations.

Specifically, the ABC study is a research study, first and foremost. It asks research participants to contribute much of their medical data. Some data resulting from medical tests, like an abnormality on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scan, will be revealed to the participant. But others, like biological markers from a positron emission tomography, (PET) scan still undergoing investigation, may not be. It’s important for the participant to understand this, going into the study.

“Will Harry be your study partner?” Watson asks. “Yes,” Shulan replies with a warm smile.

Marianne Watson, RN, (center) retired in July 2018 after serving the Penn Memory Center as senior research nurse since its inception 25 years ago. At the time of her retirement, Watson was the only person to have met and engaged with every single research participant in the ABC study. “The NACC program and the Penn Memory Center is very much Marianne,” PMC Co-Director David Wolk, MD, told research participants at the annual Research Partner Thank You Luncheon earlier this year. “Marianne has been such an integral part of it over the years, and many of you identify our program most with her.” (Credit: Joyce Lee / Penn Memory Center)

For the ABC study, a person who knows the participant well is critical because that person can speak to the participant’s memory and thinking skills, mood, and functioning. What’s key, if the participant does experience cognitive decline over the course of participation in ABC, is that the study partner is able to point out signs of decline and, in more severe forms of dementia, speak up for the participant.

Despite the focus on health data and logistics, Shulan and Watson’s conversation soon turns more personal.

Shulan does not have Alzheimer’s disease, but she wonders if she’ll develop it in years to come, if she’ll inherit it from her mother.

“Maybe I was losing my mind, which was always so sharp,” Shulan says. “My mom could never admit she had Alzheimer’s… but I’m not like that.”

Shulan discusses what she describes as the dulling of her cognition, like forgetting an actor’s name with friends. But clinicians assure her, for now, it’s a sign of normal aging.

Watson wraps up her interviews with both Shulan and her partner, who comes in later for his portion of the visit. For two and a half hours, they go through a lot: Shulan’s family history with Alzheimer’s disease, her current complaints of cognitive strain, and the battery of neuropsychological testing. After the marathon, everyone is ready for lunch.

Diving into the Data

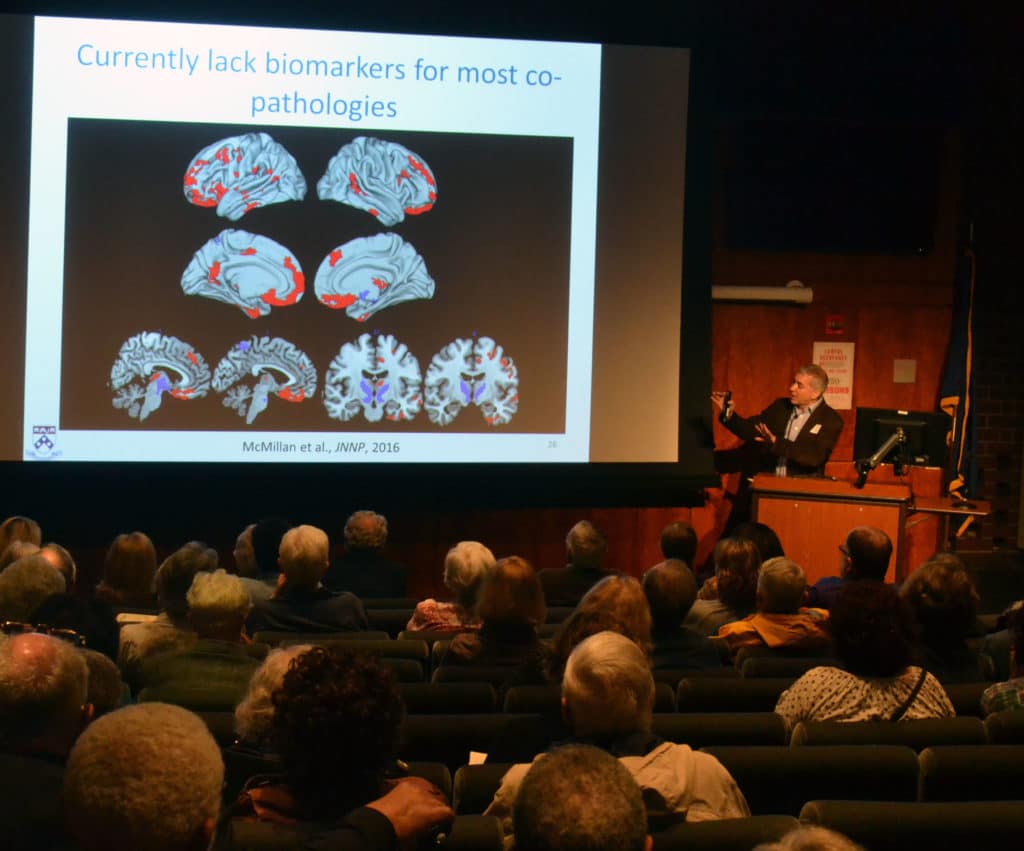

Co-Director David Wolk, MD, presents ABC data at the 2018 Research Partner Thank You Luncheon. (Credit: Terrence Casey / Penn Memory Center)

“The ABC study asks a lot of its participants, but each part is necessary,” David Wolk, MD, principal investigator for the study, explains. “For us to really get to the underlying aspects of Alzheimer’s disease, we need to take a closer look at the medical data provided by the research participants: cognitive tests, the brain scans, the reports from the study participants and partners. That’s where our research begins.”

For these reasons, an MRI scan is one of the most fundamental requirements for the ABC study. Additional studies throughout the year may also include PET scans, lumbar punctures, and further cognitive testing.

Terraine Smith also participated in PMC’s Typical Day photo elicitation study. (Credit: Damari McBride / MyTypicalDay.org)

Terraine Smith, five-year veteran of the ABC study, says she doesn’t see requirements like the MRI as burdensome. When she goes in for her scans, the technician plays music for her. “They know I love Barbara Streisand,” she laughs and says.

During an MRI scan, a strong magnet creates detailed images inside the body, allowing doctors to differentiate between forms of dementia and normal aging. Although the tight space and loud noise may deter some participants, MRI scans are vital for understanding the brain.

Beyond the MRI, Smith has participated in all the tests and studies ABC has asked of her. She has even enjoyed the long wait before a PET scan.

PET scans use a radioactive tracer that is injected and binds to specific molecules in the body. After the tracer is absorbed, which takes about 60 to 90 minutes, the body is scanned for the presence of these molecules. For the ABC study, the tracers used are for amyloid and tau proteins, which accumulate in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease.

Smith reflects on her experience with the PET scans. “You have to wait a bit after the injection,” she says. “I got some time to relax, personal time. Then I went to sleep.”

In her dedication to the ABC study, Smith has even had an lumbar puncture (LP). During an LP, a hollow needle is inserted between the vertebrae in the spine to remove a sample of cerebrospinal fluid. The sample is then analyzed for amyloid and tau protein levels.

Smith says she can understand why some people are hesitant to undergo the procedure, but said it wasn’t a problem for her. Above all, Smith’s efforts are contributing to the important data Dr. Wolk and his team are collecting to advance Alzheimer’s disease research.

Reasons and Representation

In 1999, Florence Collins-Hardy’s husband was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). That was when she first became involved with the PMC. After he passed away in 2005, Collins-Hardy stayed connected with the PMC community and eventually enrolled in ABC herself.

Collins-Hardy is steadfast to her commitment to the study: “to the end and then some,” she says.

For Collins-Hardy, this commitment has led her to agree to donate her brain to the study. “It’s the only way to connect the biological to my psychological tests,” she explains.

Brain donation is an essential part of the ABC study. This, compiled with the cognitive tests, MRI and PET scans, and LPs, will provide researchers with better understanding of the brain in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Whether an individual has Alzheimer’s disease upon entering the study, develops it during, or remains cognitively normal throughout, the brain sample can reveal how the disease works at a detailed, biological level.

Collins-Hardy’s other reason for enrolling in the study is simple: “We need more people of color in research,” she explains. “I tell other people of color… get involved in research. It’s going to help us to have medications suited for us.”

Collins-Hardy is enthusiastic and even has a speech prepared to convince others to join the research effort.

Smith says she feels similarly. She says her contribution is small but that she is compelled to help her fellow man. “It’s the only thing I can do, so why not?” Smith also enjoys her interactions with the research coordinators and clinicians: “They make me feel like a human,” she says.

After explaining her reasons for participating in ABC, Collins-Hardy notes, “My experience at PMC has been wonderful, meeting different people. But it’s also informative. They keep you up to date on new meds and improvements. I can’t say enough positive things.”

As part of the ABC study, participants join the broader PMC community. This includes regular informational updates from the team, such as weekly newsletters and annual magazines, in addition to an invitation to the Thank You Luncheon held every year for participants to learn about the latest in Alzheimer’s disease research. It’s a way for PMC to give back to the participants that give to the study.

After the Diagnosis

In the course of participation in the ABC study, if a participant is later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or another neurodegenerative disease, he or she can be brought into the PMC clinical realm. ABC participants also have access to PMC’s team of social workers and growing suite of programs such as psychotherapy, Cognitive Fitness classes, and Memory Café.

“If something happens with my brain, [PMC is] the first to help,” Smith says.